Artists and Parks Canada heritage interpreters, Justin Apperley (left) and Miriam Behman, with their field camera

Photography played a key role in the history and mythology of the Klondike Gold Rush. The photographer’s lens bore witness to the thrum and commotion of the stampede, along with the turmoil it wrought. The impacts of this era are something Parks Canada interpreters share with the thousands of visitors that come each year to the Klondike National Historic Sites in Dawson City.

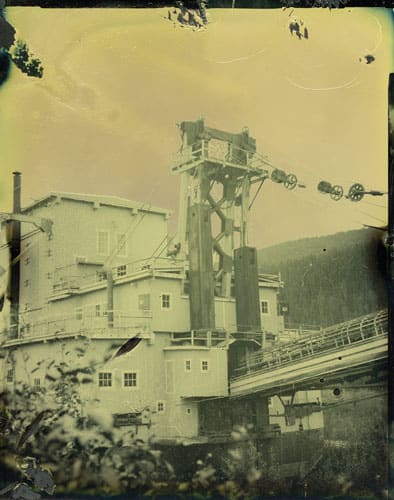

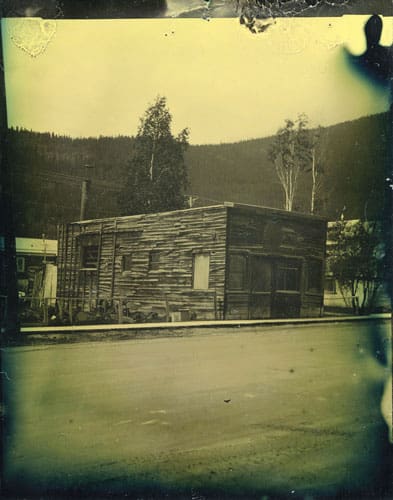

In a season like no other, Parks Canada staff were challenged this summer to find new ways of connecting people with the Klondike story. Heritage interpreters Miriam Behman and Justin Apperley saw one answer in a tintype photography kit collecting dust on a shelf. Behman, a NSCAD photography grad, has been experimenting with darkroom equipment since early adulthood. Apperley is an interdisciplinary artist with an MFA from the Glasgow School of Art and a penchant for photography and printmaking. Both look for ways to bring their artistic interests into their interpretive work. The two set out to create a series of photographs reminiscent of those by prominent Gold Rush photographers Eric A. Hegg, E.O. Ellingsen, and Clarence and Clarke Kinsey.

During the later part of the 1800s, the new field of photography was exploding with ingenuity and invention. In the pursuit of “drawing with light,” there were now myriad techniques for fixing images to glass, metal, paper and celluloid, and improved camera designs for portability, with sturdier boxes and folding bellows. Amidst this evolution, the Klondike Gold Rush was kicking into full swing. The ensuing stories of wealth and adventure captivated the world and sparked tens of thousands of mostly depression-weary Americans to try their luck in the goldfields of the Yukon. Along the treacherous routes to the Klondike, photographers followed in the stampeders’ footsteps—by turns muddy, rocky and frozen—living and documenting the Gold Rush experience.

Photographers captured scenes that would become enduring evidence of the impacts of this time, including First Nation gear packers adapting to the influx of foreigners on their traditional trading routes; the bodies of man and beast beaten by avalanche, terrain and starvation; a Hän fishing village as it stood before being displaced by cabins and a red light district; the environmental destruction brought by the insatiable need for firewood, shelter, transportation and food; portraits that glow with the triumph of arriving and surviving; Front Street bursting with Fourth of July revellers; a load of pay dirt despite all the odds; the iconic image of the progressive and insightful Chief Isaac, steadfastly guiding his people into an uncertain future.

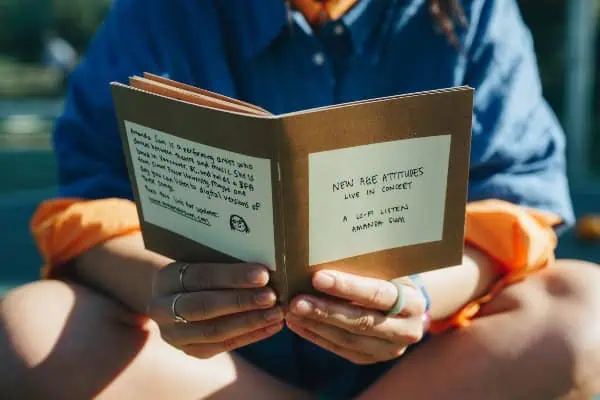

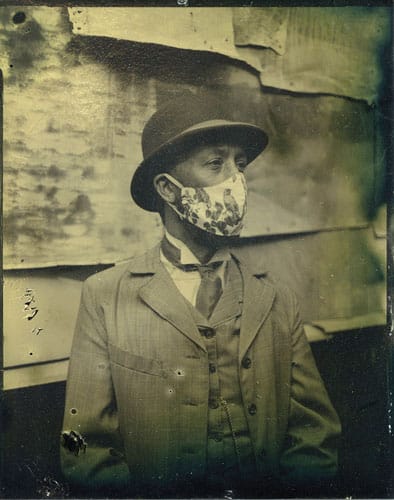

Parks Canada’s 2020 exhibit, Silver Linings, connects to the importance of photography during Dawson’s gold rush years. Behman and Apperley used dry-plate photography techniques, popular in the late 1800s, that involve coating a 4-inch by 5-inch metal plate with a photosensitive silver emulsion, exposing the dried plate in a field camera, and revealing the image through a series of chemical baths. Every photo in the 30-image series depicts a historic Parks Canada place, some featuring staff in period costume and face masks. The face masks, part of the project’s safety protocol, drew an interesting line between this historical photography and the modern pandemic experience.

Apperley notes that we are also living in “a significant moment in history … and Yukoners are so used to seeing Klondike photography, one of the pillars of our northern collective culture.” The mix of the two added a layer of complexity to conversations during the Riverside Arts Festival and Culture Days where the exhibit was featured. The project itself would not have been possible for the two interpreters during the busyness of a regular tourist season (recall: dust and shelf).

Behman values the opportunity to incorporate historical photography into her interpretive work. “I’m always interested in including the history of photography in the programs that we do because it’s significant to the history of the Gold Rush.” Parks Canada is grateful for the community that came together around this project, including the interpreters who were willing to share their talents and the local experts who helped troubleshoot challenges.

After a number of struggles, Behman recalls the experience. “Justin and I were standing over the vat and an image started appearing, it was so exciting.” Perhaps a bit like finding gold.

Conservation Photography