Yes, they know it is cold in the Yukon.

The cast of Studies in Motion has been checking out the temperatures here daily.

Yet they will all be nude sometime during the play when it shows at the Yukon Arts Centre March 24 to 27.

“I was already nude on that stage a couple of months ago,” Jonathon Young says bravely. “It was fine.”

That would have been the occasion of his solo performance in The Invisible Life of Joseph Finch.

This time, he has a lot more company as he will be joined by 11 other cast members as they examine the life of pioneer photographer, Eadweard Muybridge.

“You couldn’t do a show about him without nudity,” says Young over the phone during a break from rehearsal in Vancouver.

If you see a series of vintage still photographs of a nude man or woman performing a mundane task, it was likely taken by Muybridge.

“The fascinating thing of these motion studies is that the people are completely naked and doing acrobatics, walking up stairs, throwing spears, spanking children, and they all look slightly self-conscious about it.

“They weren’t so different than us.

“You then get past the portrait, where the subject is staring into the camera and all dressed up in button vests, and you see them as more vulnerable.”

And the question of the day, as it is so often today, was, “Is this pornography?”

“He got around it by claiming this is a scientific study and we would understand the world better,” says Young. “Doctors and scientists would use these studies.”

And yet Muybridge would push the boundaries by recording a woman beating another woman with a broom, two women flirting and opening the chest of a turtle to see its beating heart.

“Kevin [Barr, the playwright] is playing with this man who is trying to understand human nature by breaking it into small, reliable pieces,” says Young, paraphrasing a line from the play.

And just as Muybridge examined the nude within a scientific context – filming nudes walking in front of a grid – the play has a parallel effect of making the audience comfortable: “None of it is sexual nudity and it is something you get past quickly,” says Young.

“Let’s put us in a catalogue with all of the other animals and see what we have in common … see what unites us.”

This pre-occupation of Muybridge’s did, after all, begin with the study of a horse’s trot. Did all four hooves leave the ground at one time?

Leland Stanford hired Muybridge to settle the question (legend has it there was a $25,000 bet involved) and, with the innovation of a chemical developers and an electrical trigger for a shutter, he was successful in contributing toward the development of motion pictures.

His own Zoopraxiscope projector was used to show moving pictures at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition and is considered to be the first commercial movie theatre.

It is this blending of science and culture that has found another parallel with Studies in Motion: Robert Gardiner, a professor with the University of British Columbia’s Department of Theatre, Film and Creative Writing, approached Electric Company Theatre about his vision of using film projectors as a lighting source for the stage.

The Muybridge story was already being considered and was determined to be the ideal play to join the two ideas.

Writers and designers and choreographers worked together to bring the play to the stage.

“The play is set on a grid,” says Young. “It goes back and forth from the well-ordered scientific approach to understanding ourselves and the chaos of his past actions.”

These past actions include killing his wife’s lover, claiming he was innocent from a well-documented brain damage, but getting off due to “justifiable homicide”.

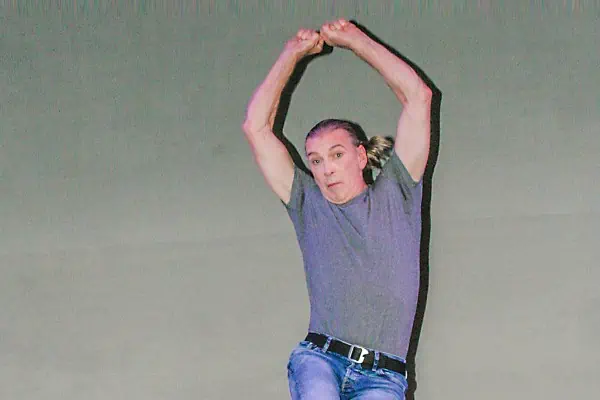

And, although none of the actors are dancers, there are “physical sections that are dance-like” that were built in, says Young. These were choreographed by Crystal Pite.

Studies in Motion begins its national tour in Whitehorse March 24 to 27 at 8 p.m. at the Yukon Arts Centre. Tickets are available at the Yukon Arts Centre Box Office and Arts Underground.