If humanity for some reason disappears, what will become of Earth’s other inhabitants? This is what David Curtis invited us to consider in Shall Inherit, an installation that was exhibited in the Yukon Arts Centre (YAC) Community Gallery during the Available Light Film Festival.

Shall Inherit is the eighth in a series of seven similarly themed projects called Search though we might, we may never see beyond the horizons of our imaginations. The idea that our imaginations are boundless holds the promise of infinite creative potential, even in a world turned upside down. For Curtis, the pandemic was a time to immerse himself in his surroundings in and around his home in West Dawson. It’s been an incredibly productive time for him, and he said, ”Periods of isolation have helped hone ideas I’ve been carrying with me for decades.”

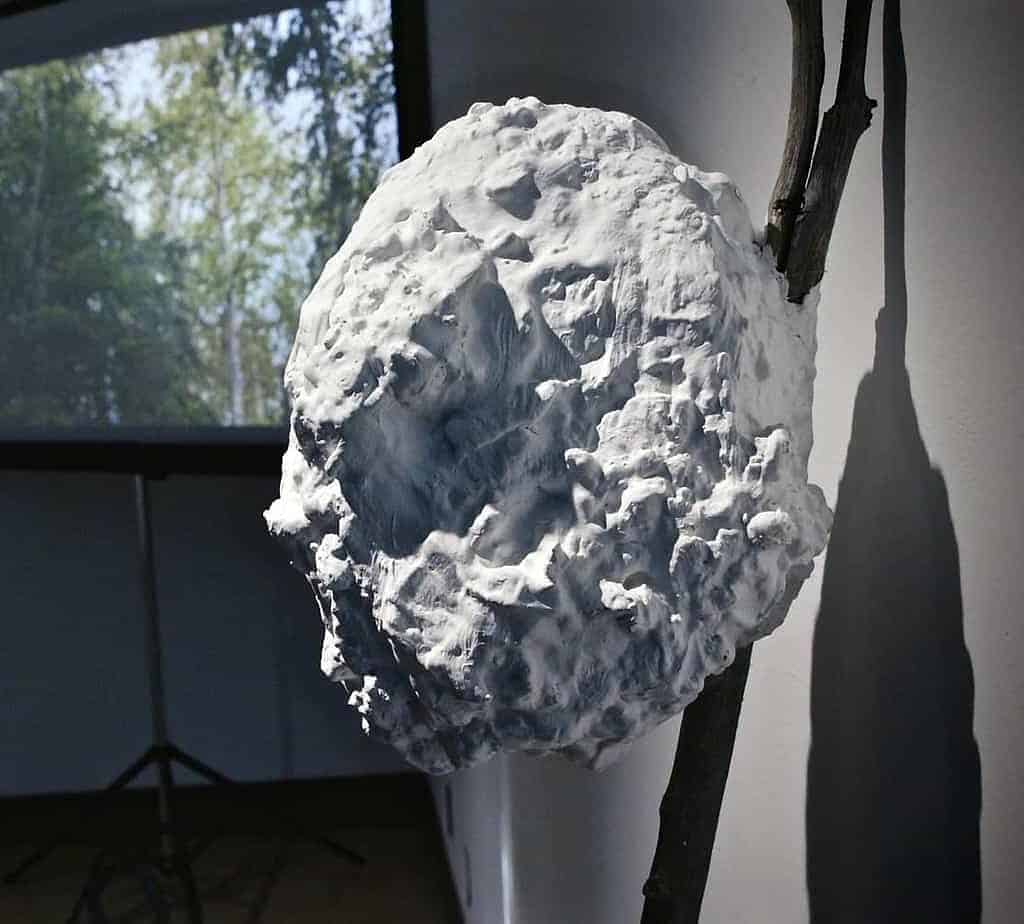

For the YAC installation, a bulletin board announced the show, with SHALL INHERIT written out with clear acrylic push-pins and surrounded by colourful artificial flowers and balloons. Curtis intended the effect to be like coming across an unexpected sideshow at the midway. Once inside the space, the mood became markedly more dark, mysterious and strange, with shades of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (a 1920 German silent horror film).

The gallery was made to resemble a deserted room, furnished with a number of objects placed together with an odd logic and eccentric aesthetic. An old record player spun a wonky album made from the cross-section of a tree. A black, oily painting hung on the wall above a cake covered in goopy white-fondant icing, which had a dead bird placed carefully in its center. A pipe, leaking a substance that looks like oil, leaned over an old chair. A second dead bird was hanging by one leg from a free-standing shelf.

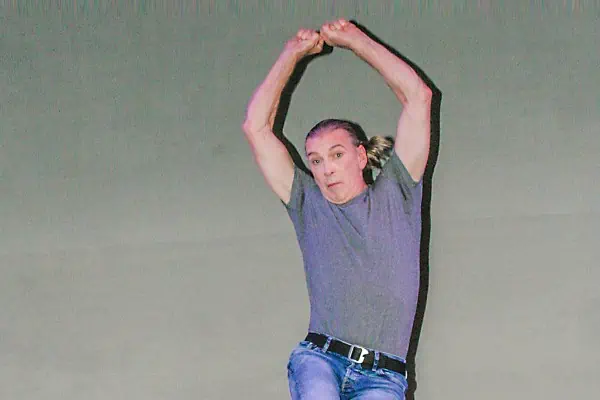

What could the objects and their peculiar placement possibly mean? Ultimately, their significance depended on the viewer. Curtis said he used these elements almost like language, but that they had no inherent meaning. His intention was to create a “stage for a dialogue between the objects themselves and their relationship; and then the viewer bringing their own experiences and knowledge and understanding of the world and having a visual conversation, to some extent, or some sort of conscious or unconscious conversation with the objects in this new context.”

Curtis saw the room and its objects as inward-looking, reflecting an interior character. This interiority was interrupted by a screen lit up with moving images drawn from the outside, natural world. The film showed brief glimpses into the lives of beings other than humans. Curtis used intimate close-ups to contemplate the fates of flies, ants, spiders and birds. Some were thriving, some were struggling, some were dying—others were already dead. There were also forest scenes—trees, wildflowers and streams—but the latter were scarred by discarded oil barrels and what seemed like toxic waste that was turning the burbling water into bubbling brown foam.

The film’s images acknowledged the rhythms of the cycle of life and death, which Curtis said he witnessed as a boy visiting farms. The film was also reminiscent of nature shows of the 1970s, which Curtis watched as a child. However, Curtis avoided the sensational, narrative structure of those TV programs and instead took a more-intimate, non-narrative approach. A soundtrack, featuring the eclectic music of contemporary composer Andrew Norman, provided a dramatic arc for the film, which had no obvious beginning or end.

Other than the polluted stream, the film’s only suggestion of humans was the presence of household pets—a cat luxuriating in the sun, and two dogs lying on a sofa. Curtis said that he has an interest not only in how we see non-human creatures, but in how they perceive us. The expressions of the domestic animals in the film, in response to the human filming them, ranged from knowing indifference (the cat), to vague suspicion and boredom (the dogs).

All the creatures in the film are, perhaps, like the meek who will inherit the Earth. In reference to the installation’s title, Curtis said, “What’s the world going to inherit? What’s the next generation going to inherit from the things we are doing now to the planet? And then, if we were to disappear for some reason, what would the things—the animals, the flora and fauna left behind … What would they inherit from us?”

Curtis fears that, during times of pandemics and conflict, there is “a fading concern for the rest of the world, the non-human world.” He asks us to see beyond our human-centric perspective. His recent projects are investigating this alternate point of view, which has deep respect for nature’s mystery, strangeness and beauty. He urges us to remember our “poignant relationship” with the non-human world, and to recognize ourselves as “just one species in the biosphere” that we share with all living creatures.