If I did not believe that reason could bring something of value to the imaginative process I would not bother writing about art.

I offer my observations in order to beat down a path in the snow to the art shows, to encourage my readers to see them, and to offer language as a tool they can use to form their own opinions.

The controversy around the current show at the Yukon Arts Centre Public Gallery, Sleep of Reason, began with the ArtsNet post hoping to engage people with the show.

The posting began with the question, “What do you think of when you see this Francisco Goya painting and hear its title: ‘The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters’?”

It then went on, “Goya was critiquing Enlightenment Reason, scientific knowledge, Capital T-Truth. Jennifer Cane, curator of this exhibition, says, ‘What I see in Goya’s work is essentially that strict rationality produces madness— and this could be seen as the exhibition’s central thesis.'”

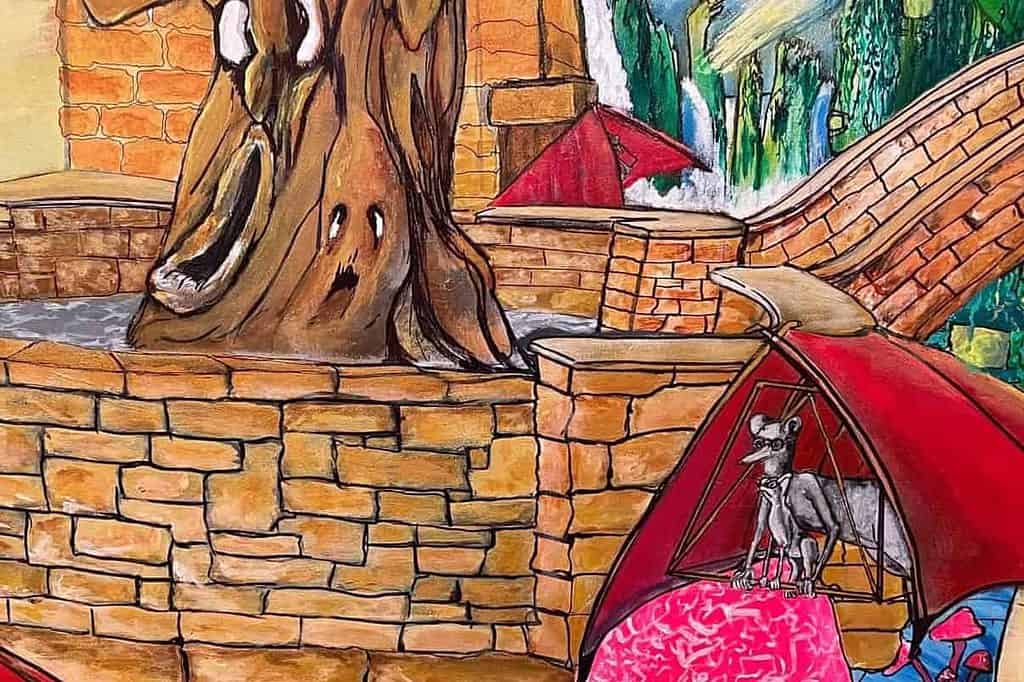

Joseph Tisiga’s Preparation for Utopia, watercolour on paper, 2012

A couple of Artsnet readers – including your reviewer – objected to this interpretation, as the work is more commonly understood, for some good reasons, to beseech Reason to wake up and act as a better guardian of reality.

In the end, this “central thesis” isn’t mentioned in the curatorial statement you can pick up on your way into the exhibition.

In that text, the curator takes as her adversary the notion of the artist as an impractical, childish dreamer. She maintains that artists “articulate and illustrate very practical and concrete social dimensions… to educate, to change society, and to change the world through their work.”

It’s interesting to observe the similarities between Rosemary Scanlon’s and Joseph Tisiga’s work. Both use images of animals in watercolour.

Tisiga often includes bears in his work, though he also uses human figures and First Nations ceremonial items. Scanlon offers us iconic images of a fox and an owl, in flat designs on red and blue backgrounds inspired by medieval tapestries.

In the contrast with Goya’s piece, which came out of a time when animals had set symbolic meanings (the dog, fidelity; the bat, ignorance, and so on), Scanlon and Tisiga’s animals evoke a more open set of responses to a contemporary audience.

Both Scanlon’s and Tisiga’s works seem to give us a glimpse into hidden stories about eerie or violent powers at play in our society. They seem to arise from a preconscious mind, one we couldn’t get to by means of reason alone.

Jim Holyoak’s ink drawings of bats emerge out of brushy black backgrounds. Some are labelled with their scientific names.

Viewing them in the light of his loving observation, it seems unfair that they should have represented ignorance, when it’s just that their senses are configured differently from than ours. They can see in the dark with their ears.

Shuvinai Ashoona’s drawings include ulus, ice floes and a contemporary sense of anxiety. “Checking Just Checking” contains many clocks with no hands. A monster with clocks for eyes and down his throat emerges from the low centre of the composition.

Jeff Ladoceur’s drawings depict a single figure in a cartoon style, split in two, looped in a tree, or running in a gerbil ball of elongated versions of himself. Both seem to be drawing the world inside their heads.

Other works are more about interactions. Nadia Moss’s drawings depict two figures acting on each other in mysterious ways. Red fingertips bleed into the other figure’s torso.

Jen Weih’s installation includes a video of image clips from web browsing, floating on a dark background like space junk. They collide, deflect off each other, sometimes miss each other entirely.

A sequence of transparent illustrations by Nadia Moss

Sonja Ahlers’ installation uses a spiral staircase built by a fourth year Yukon College carpentry student as a training project. She’s a collage artist: she loves to place things beside each other. This staircase is one giant found object

The piece includes stacks of “Sweet Dreams” teenage fantasy, a floor of pennies, a slowed down Kate Bush video, fine gold thread, and hanging golden nooses. We’re invited to add these things up for ourselves.

In addition to her drawings, Moss has created a sequence of transparent installations on the walls that draw from her interest in earthworms. One of them uses only clear acetate mounted on pins. It has been cut into shapes and scratched.

In the shadows cast by each piece, earthworms and nude human figures without breasts or penises fall or fly, a descent into hell or ascent into heaven, who can tell? Look closely, though—there seem to be some disembodied penis and scrotum shapes in there with them.

David Horvitz’s piece includes a sheet of paper for every day of the exhibition. Most of them are grey right now. Every morning of the show he will get up and record what he can recall of his dreams, and they will be posted there.

You can subscribe to receive his dreams by email at www.davidhorvitz.com

Sleep of Reason continues until May 19. Its catalogue will become available in April.