Artist Esther Bordet visits the same Himalayan summit as her great-uncle, to create a graphic novel based on his travels.

In 1953, a French geologist named Pierre Bordet applied to accompany a group of French Alpinists on expeditions to Makalu, a summit in the Himalayas. When his application was accepted, it was a life-defining moment. After the initial expeditions, which took place in 1954 to 1955, he’d go on to spend two decades conducting research and mapping parts of Nepal and Afghanistan.

Thirty years after Pierre Bordet set off for Nepal, his grandniece, Esther Bordet, was born in Paris. Like her great-uncle Pierre, Esther had an interest in rocks and volcanoes. As a child, she spent a lot of time in an area of France that had numerous fossils.

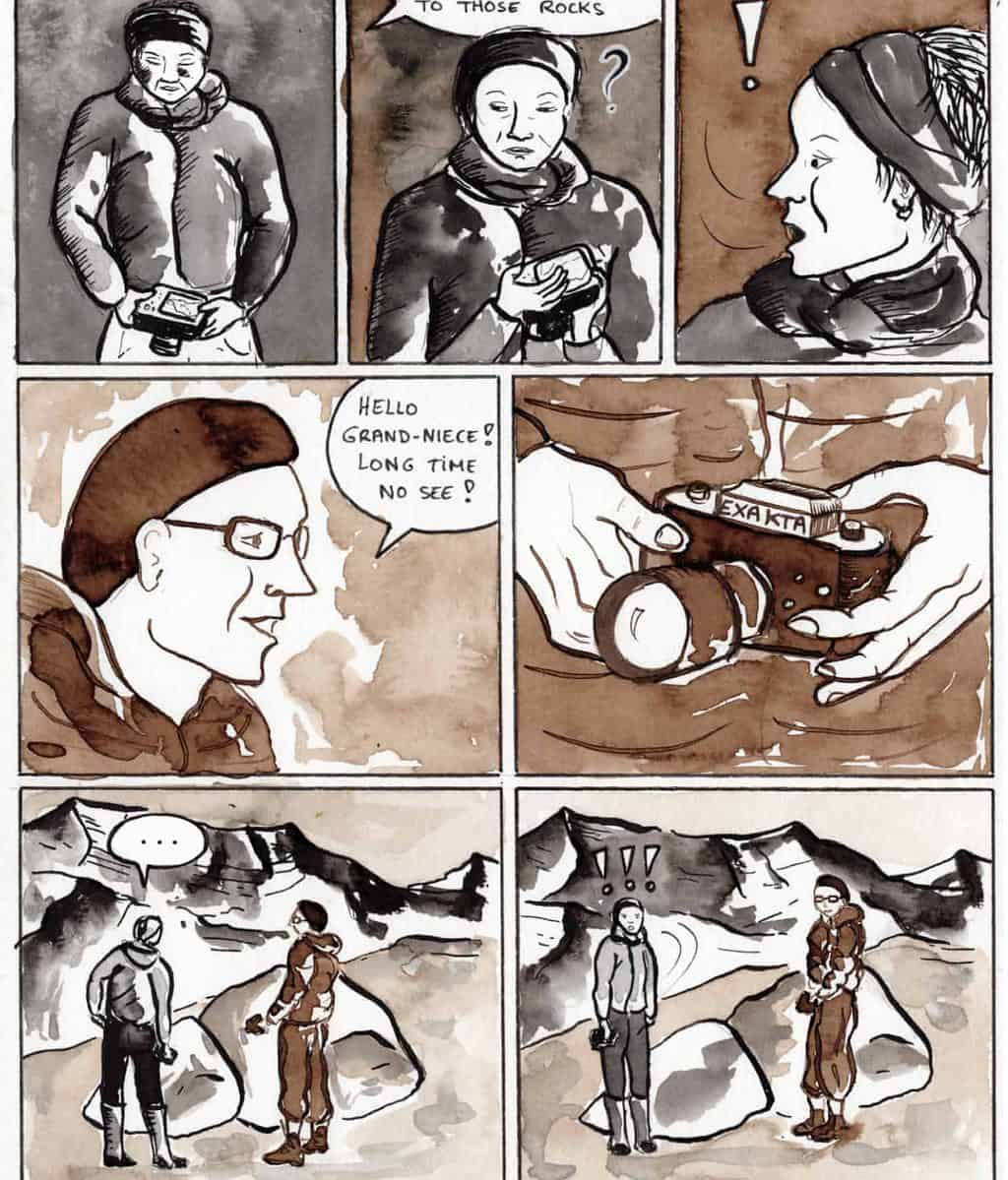

Esther was introduced to Pierre’s adventures through slide shows of images he’d taken during his travels. She was also given a copy of his travel notes, Mémoires de mon Marteau, which his family had published.

By the time she first read the book, Esther was herself a geologist. She was working in central B.C., “where, in her words,” the fieldwork “was horrible.” She found an affinity with her great-uncle through his writing, which described the extreme difficulties he had working in the Himalayas. His experience made her feel less alone.

“I actually felt like my life was not that miserable after reading his book,” she said.

Eventually, after years of working as a geologist, Esther took a leap of faith that would change the trajectory of her life—she quit her job at the Yukon Geological Survey, to become a full-time artist.

Esther now works as an illustrator, to support herself, but comics are her real passion. And Pierre Bordet’s travels and work have become the subject of her first graphic novel project.

The decision to base her first big project on her great-uncle’s adventures came as a revelation to Esther, along with the realization that, contrary to what she believed, she could be a storyteller—a creative writer—as well as a visual artist.

“I always thought I was really terrible at telling stories,” she said. “I had never done it before.

“One morning I literally woke up and said, ‘Wait a minute, I do have a script basically already written,’” she continued, referring to Pierre’s memoir.

Other sources for her graphic novel are the many colour slides that Pierre took and which a family member digitized. The images are of exceptionally high quality and provide visual references of the places Pierre visited and the people he met, including the group of Alpinists he originally traveled with to Makalu.

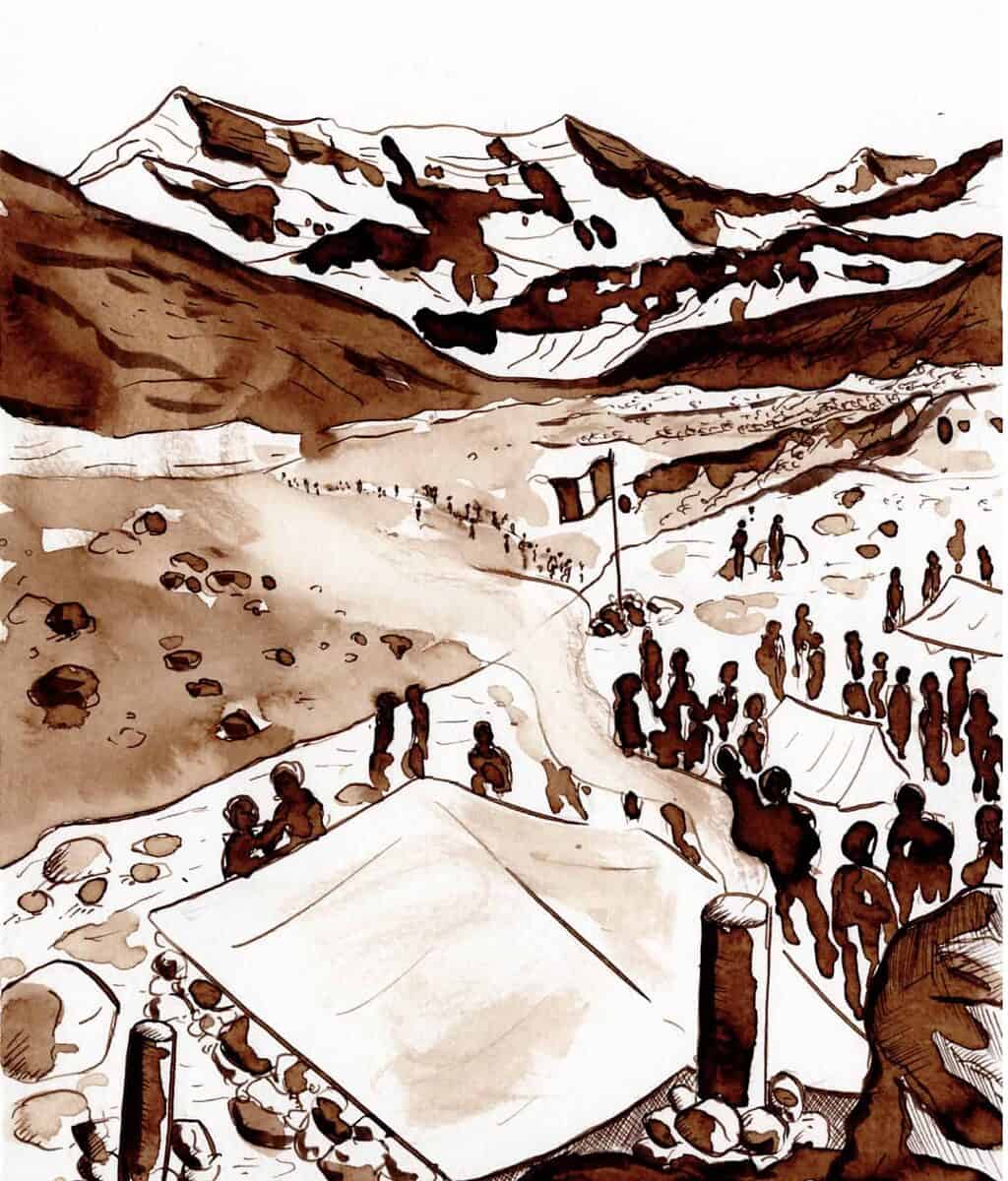

As well, Esther traveled to Nepal in 2019. She went to Makalu and found the places that Pierre had been. In one instance, she stood on the same spot where Pierre would have stood and took a photo of the same view he had photographed 60 years ago. Remarkedly, Esther found that very little had changed.

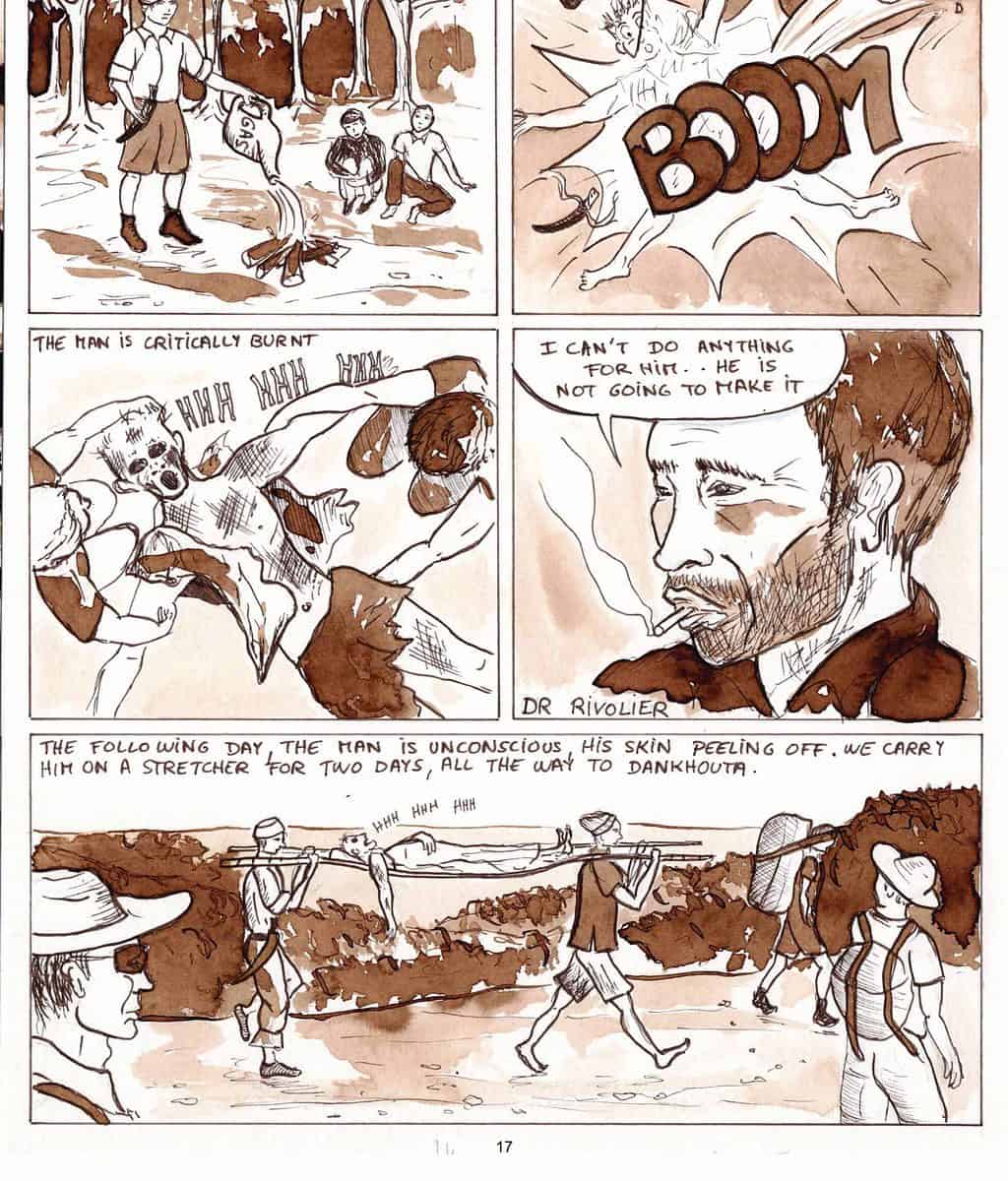

Her initial drafts for the graphic novel included two storylines: one of Pierre’s experiences in Nepal in the 1950s (rendered in walnut ink); the other focusing on Esther’s own travels in the region in 2019 (drawn with black India ink). Esther was dissatisfied with her first attempt and found the script to be “very boring.”

Over time, she had the idea of imposing herself in an imaginary time frame where she could interact with her great-uncle and the Alpinists of that era. This foray into a fictionalized, non-linear time and space gave Esther the freedom to imagine interactions with Pierre and to explore the “burning questions” she had about the expedition and its socio-political significance.

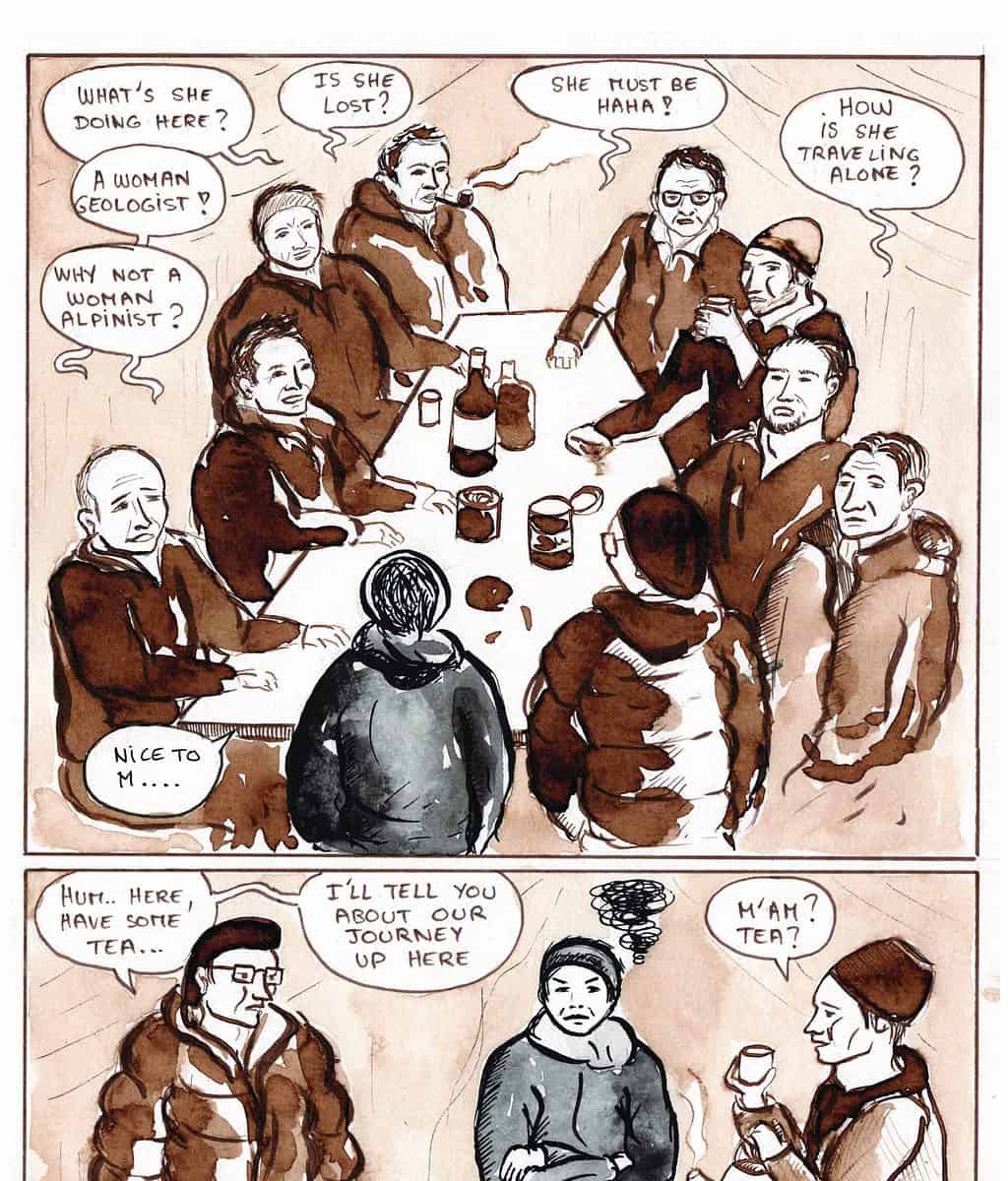

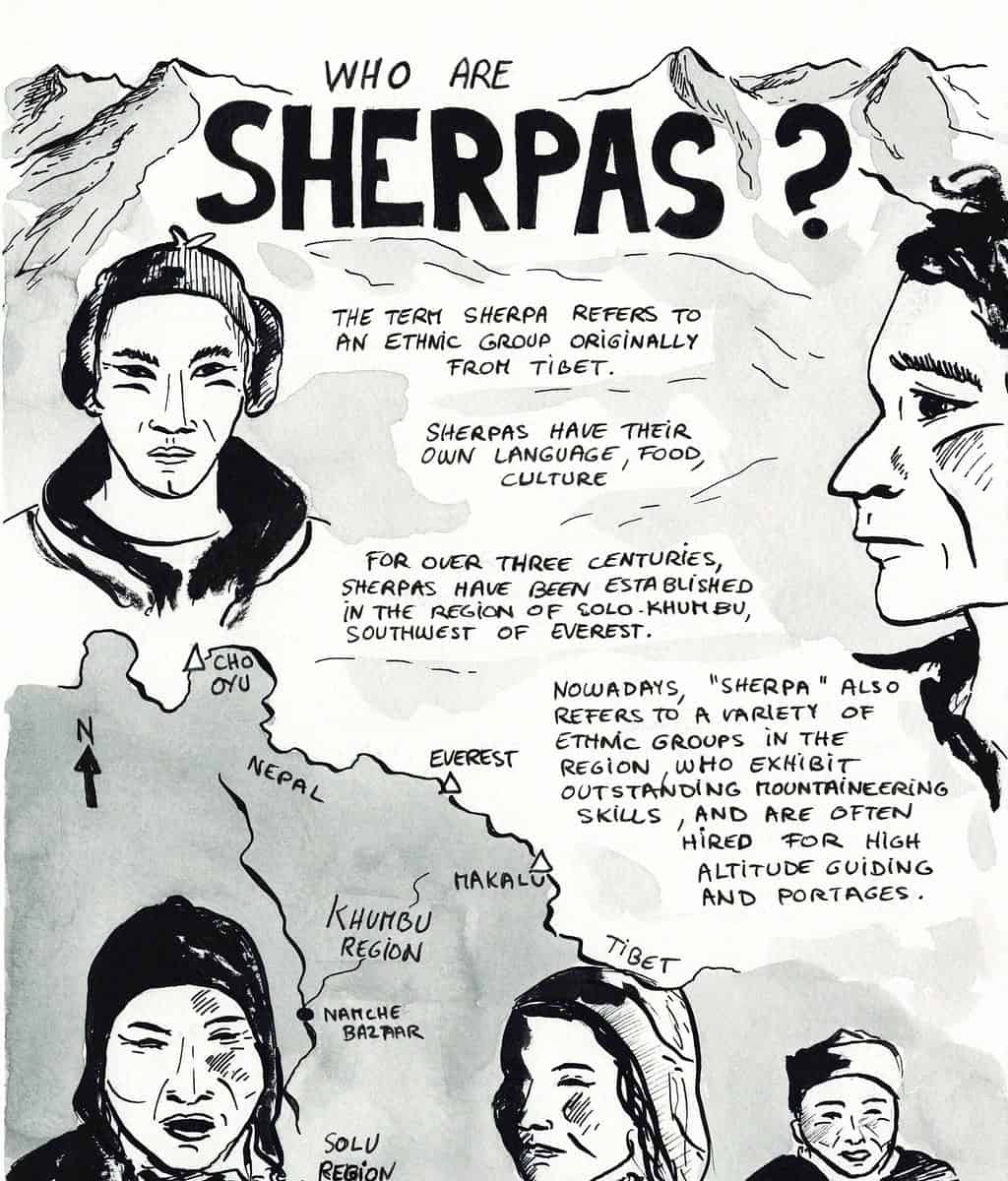

For instance, the expeditions were tied to European power struggles, as colonizing nations vied to be the first to “conquer” the eight big summits in the Himalayas. The French Alpinists, led by Jean Franco, were part of that process. Esther found, through Franco’s own writings, that the mountaineers were incredibly condescending to their porters and Sherpas.

In Esther’s imaginary interactions with the Alpinists, they are incredulous to find that she is both a geologist and a woman traveling solo. Her great-uncle, fortunately, does not share these biased views.

With her background in geology and her affinity for storytelling, Esther is creating a compelling narrative that is based in both observation of fact, as well as in flights of the imagination. She does not see these two approaches as contradictory. In fact, Esther argues that there is a place for storytelling in science.

“Our imagination is our time machine,” she writes in Makulu: Thehttps://www.artsunderground.ca/exhibitions/makalu-the-story-behind-the-panels Story Behind the Panels, a comic book she created to introduce audiences to the project.

“When I took a career shift from geology to comics, I continued doing what I had always done—telling stories. Now, I use the universal language of images.”