The Friends of the Yukon Archives Society has organized a wonderful exhibit at Arts Underground on how visual arts have evolved in the Yukon over the years. It documents the lively traditions of art-making among First Nations people and, more recently, among settlers. Seeing this exhibit made us wonder what it was like to be an artist in the Yukon in earlier generations? Could someone make a living as an artist? What role could an artist play in the society they lived in? We were especially interested in two women who became well-known artists in the mid-20th century, Kitty Smith and Lillias Farley.

Kitty Smith (Tlingit names Kàdùhikh, K’ałgwach and K’odetéena) (c. 1890-1989) was born to a Tlingit father and Tagish Kwan mother (raven clan) and grew up in Dalton Post. In defiance of convention, she left an unhappy first marriage and moved to Marsh Lake to be with her mother’s family. Her marriage to Billy Smith in 1916 was happier. They lived in Robinson and Carcross and raised a family. Kitty made a good living as a hunter and trapper. Later, she sewed muskrat mitts and mukluks and sold them to soldiers, demonstrating the superiority of traditional winter gear. She was famously independent. “Should be you’re on your own,” she later said. “Nobody can boss you around then. You do what you want.”

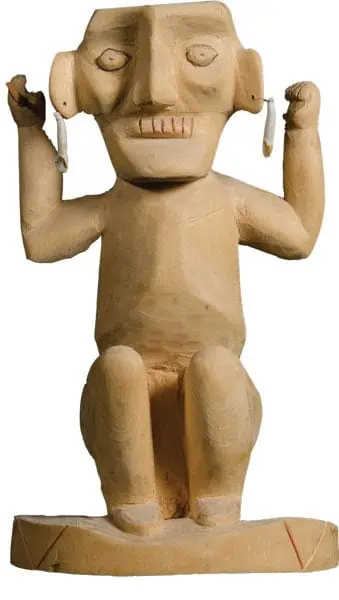

Kitty Smith’s earliest known wood carvings date to the 1930s. After that, she continued to carve for about 30 years. Each piece of her art (typically an animal figure, carved from poplar) told a traditional Tagish or Tlingit story. Her husband Billy also carved and would sometimes write short pieces that were attached to the carvings. Her granddaughter, Kwanlin Dün elder Judy Gingell, remembers both Kitty and Billy carving in front of their home in Whitehorse in the 1950s. Kitty sold her art to travellers and tourists. Her art was a source of cash income. It was also an act of cultural preservation by someone who was born before the gold rush and who became an adult long before the arrival of the settlers brought by the Alaska Highway. Starting in the 1970s, she arranged to have her stories published to preserve them for future generations.

How much art did Kitty Smith make? The Kwanlin Dün Cultural Centre purchased a piece from an Edmonton antique dealer for $1,200 in 2017, raising the possibility that other unidentified pieces may be on someone’s shelf. Some of the pieces now held by Yukon museums were not initially attributed to her. Kitty Smith’s family is currently negotiating for the return of some carvings which are now outside the Yukon.

Lilias Farley (1907-1989) had more privileged beginnings as an artist, but she too faced the challenge of having her abilities recognized in an art world that was dominated by men. She was one of the first graduates of what is now the Emily Carr University of Art and Design in Vancouver, where she formed long-time friendships and connections with other students, instructors, gallery-owners and collectors. Her paintings and sculptures were exhibited in more than two dozen shows between 1930 and 1950. She painted two large murals for the “women’s tavern” in the Hotel Vancouver. One of her sculptures was bought by IBM for the company’s New York offices.

Farley came to Whitehorse when she was 41 to help her brother Arthur and she decided to stay. She became an art teacher at Whitehorse High School and, later, at F.H. Collins. She continued to exhibit her art in Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal, but teaching became the focus of her career. “Miss Farley” is well-remembered by former students, who variously recall her kindness, worldliness, sophistication and willingness to encourage students who were trying hard, but with limited talent. Many did not know that their art teacher was a nationally-regarded artist. Artists Jim Robb and Ted Colyer have both acknowledged her influence on their work. She lived modestly, but her retirement assets included some Group of Seven paintings she acquired when she was younger. In her 80th year, a retrospective show of her work was held in the gallery of the old Whitehorse Public Library.

Kitty Smith and Lilias Farley made art well before governments started funding artists’ awards, residencies, travel grants and the like. The Massey Commission report in 1951 urged the federal government to take the lead in promoting Canadian culture, but it took time for programs for artists to be created. The first public art commissioned in the territory was Lilias Farley’s large relief sculpture “History of the Yukon” in 1955. You can see it in the atrium of the Elijah Smith Building, hanging over the main doors.

Without government supports, artists needed to make their own way, even more so than today. Kitty Smith’s art sales supplemented her income and, more importantly, her art added to the many ways in which she preserved her culture, making her an extraordinary leader and respected elder. Lilias Farley successfully sold her art and did some teaching in Vancouver. After her move to Whitehorse, teaching art became her primary source of income. Looking back, we are full of admiration for both women’s perseverance, the contributions they made to the Yukon, and the legacy of art that they have left us. n