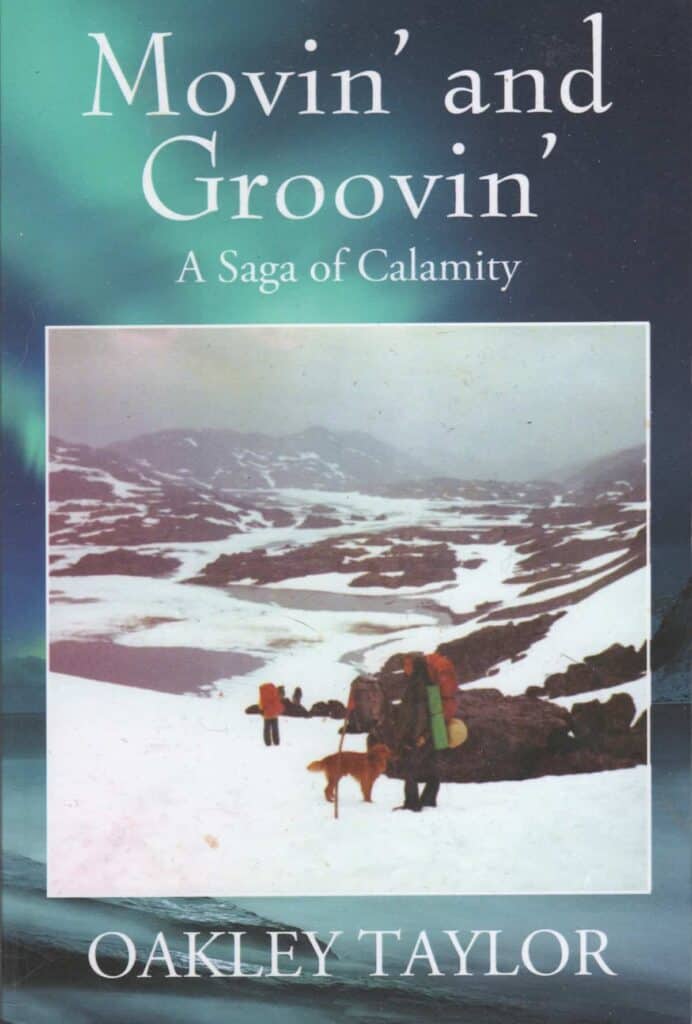

Movin’ and Groovin’: a Saga of Calamity

By Oakley Taylor

Outskirts Press

330 pages

$25.82

This book tests my understanding of the word calamity, which is usually defined as “a state of deep distress or misery.” In the course of our correspondence, I asked her why that (particular) subtitle, and she replied.

“You know, I look back on my life and I have definitely been through some very rough, tough times. When I use the ‘Saga of Calamity’ it is only as tongue in cheek, a reference to some of the thoughtless choices I’ve made (and lived through). My mother always said I took the ‘hard way’ and I think, now, in reflection, she was right. I can only say that I am glad for my time in the Yukon—it’s always a great story to tell. Some of my friends are pretty amazed, but in Yukon terms, it’s all part of the life I chose.”

Her original name was Debby, and that’s how people addressed her through the first 280 pages of the book. On the next page, she said that her name change was a homage to Barry Oakley, the bass player in the Allman Brothers Band.

Taylor has been a big music fan all her life and has carted her collection with her wherever she has gone. I sympathize.

For all her moving around, she is settled now in Bend, Oregon, where she has been since 1985. This self-published book is her way of sorting through the steps that brought her to this place and this frame of mind, which doesn’t really sound like such a calamity.

As she writes in her introduction:

“I decide that no matter what happens from this point on, I’m ahead of the game. Every day is something to appreciate. I do my best to make that time count for something worthwhile, to contribute and accomplish.”

Her early memories are of Okinawa (1961–65), where her father was in the Air Force. On his retirement, they relocated to Long Island, New York, where he worked for Grumman Aircraft, and by 1969 she had hit puberty and, in just a couple of years, had embarked on relationships that she described as “a string of trainwrecks.”

In 1973, she began travelling, first by herself and then with a girlfriend. On one of her early hitchhiking treks to a concert in Denver, she and her girlfriend scored a ride with the legendary Chicago (the band) guitarist Terry Kath. Eventually, she began a series of short-term residencies and work experiences that took her to Wisconsin, Washington State and Colorado.

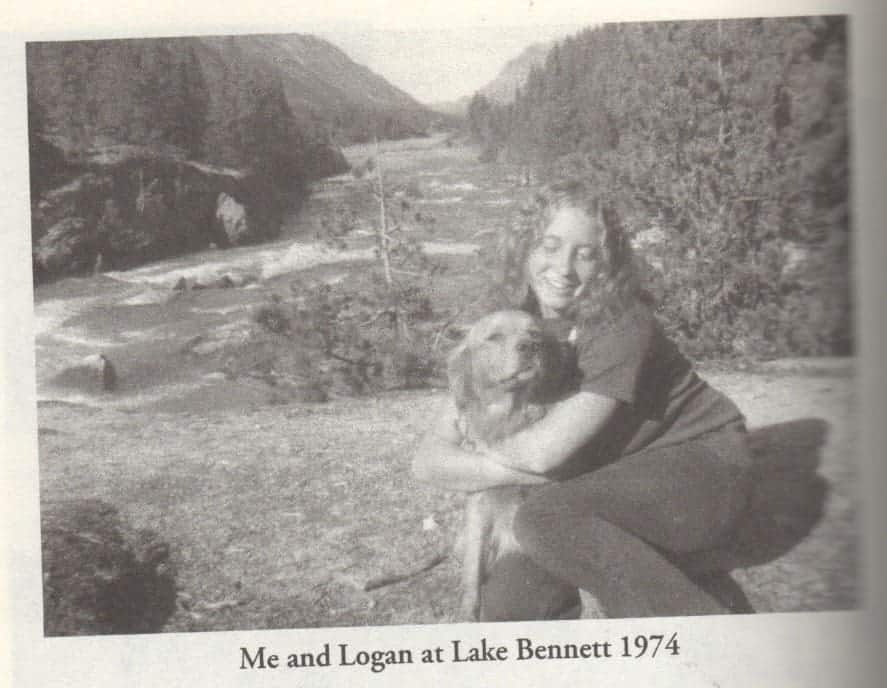

Then came her first trip into Canada, to see the Calgary Stampede, and then on to Whitehorse, after which she found her way to Lake Bennett, where she managed to work without proper credentials, for the summer of 1974, which meant she had to leave quickly before the authorities caught up to her when her job ended.

The next summer she was back, as a tourist, and soon on a trip down the Yukon River to Dawson. It’s there that she met Zeke and came up with her plan to qualify for Canadian status by getting married. They relocated to Whitehorse and she took a number of jobs there, including a stint at the Whitehorse Star in 1977. (This happened to be the year I began writing for the paper from Beaver Creek, but we never met. At that point she was close to delivering her first

son, and Zeke was proving himself to be not much of a partner.)

This might be seen as a sour-grapes assessment in a memoir, but I’ve had it confirmed by someone who knew them both at the time. In spite of that, she spoke of him fondly in the acknowledgements at the back of the book.

As luck would have it, Taylor and Zeke found work in the mines at Keno City, where their second son was born and where they almost made family life work for a time. There were ups and downs, but they seemed to be trying, most of the time. By 1981, however, they separated.

The later loss of Taylor’s dog, Logan (she had to shoot to put him out of his misery), seemed more cataclysmic than the failure of her marriage.

By 1982, she and her boys headed south to Montana, the first of several stops before Oregon, but this was where, at 27, she discarded “Debby” for Oakley, restarted her formal education in a trade school and learned that “turning wrenches” was her thing. This led to a certificate in automotive technology.

Two years later, the family was in Washington State and Taylor began a nine-month course as a farrier. The final stop was Bend, in 1984.

The next four years saw her working a number of jobs and having some short-term relationships, also buying a house and finding a more-permanent job at a particleboard plant, which ate up the next 16 years.

Not all was smooth sailing for the family, after that. Her parents died. One of the boys had lifestyle issues that got him into legal trouble. Taylor earned an Associate’s Degree in Civil Engineering, and gained grandchildren. Her adventures with them have been the highlights of her life, including a trip to the dinosaur museum in Drumheller, Alberta.

In 2018, Taylor retired. By then, she had begun what seemed to be a long-term, stable relationship with Jerry, of whom, she said, “makes my life easier, more secure … You name it, and he’ll always give it his best shot … I can’t imagine my life without him anymore.”

Oakley Taylor finished this book when she hit 66, and in the time since she first reached out to me about it, just before Christmas, she has been recovering from a broken femur, which had her wheelchair bound for a while. I can sympathize. I had some bruised ribs and muscles for about two months from an icy fall in mid December. We’ve exchanged a number of emails since then, and except for some anxiety over my publication schedule for this review, she’s been cheerful and upbeat.

Somehow, in the end, in spite of some hard times and some long journeys, her story doesn’t sound like it meets the definition of calamity, but it’s an interesting one.