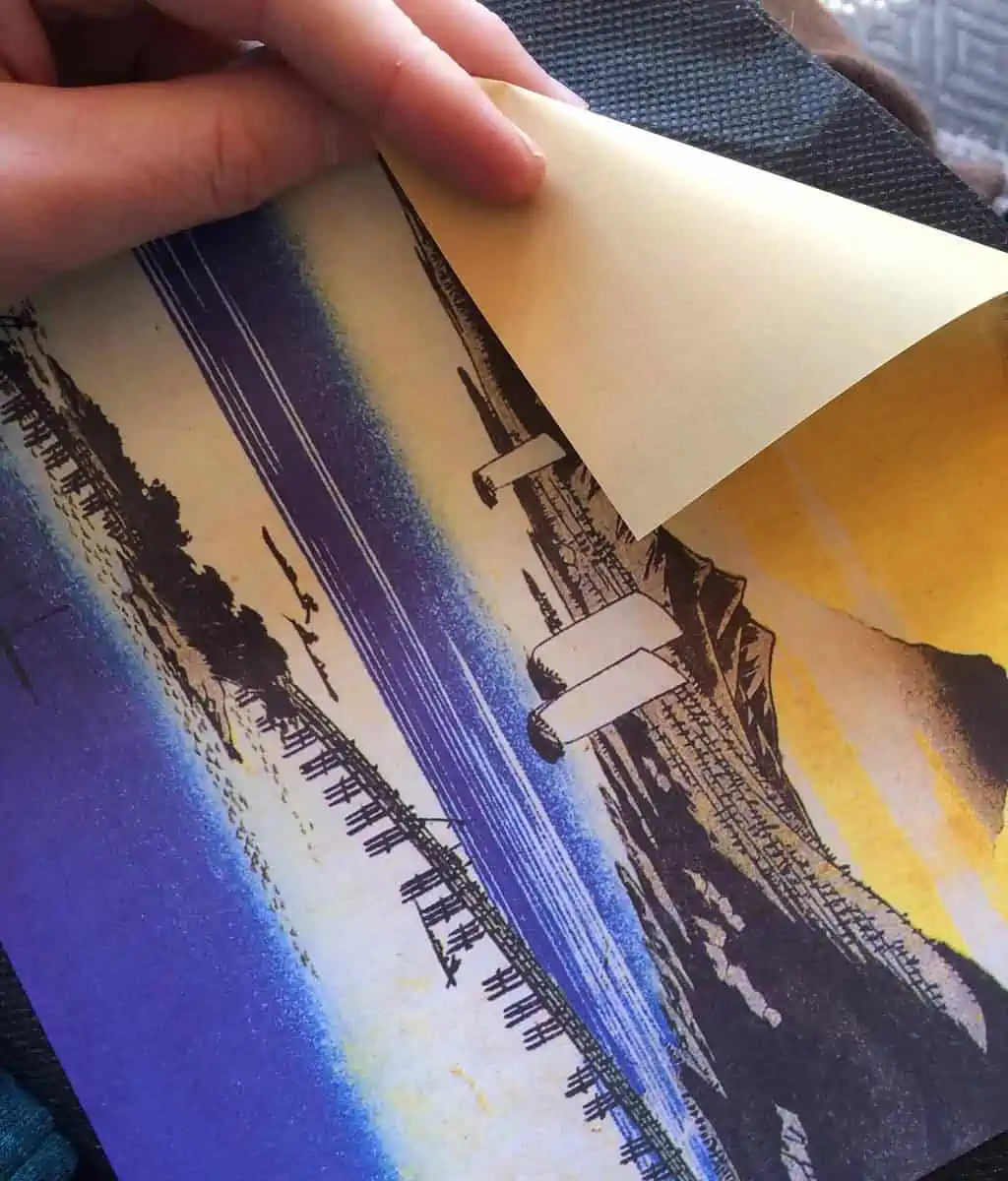

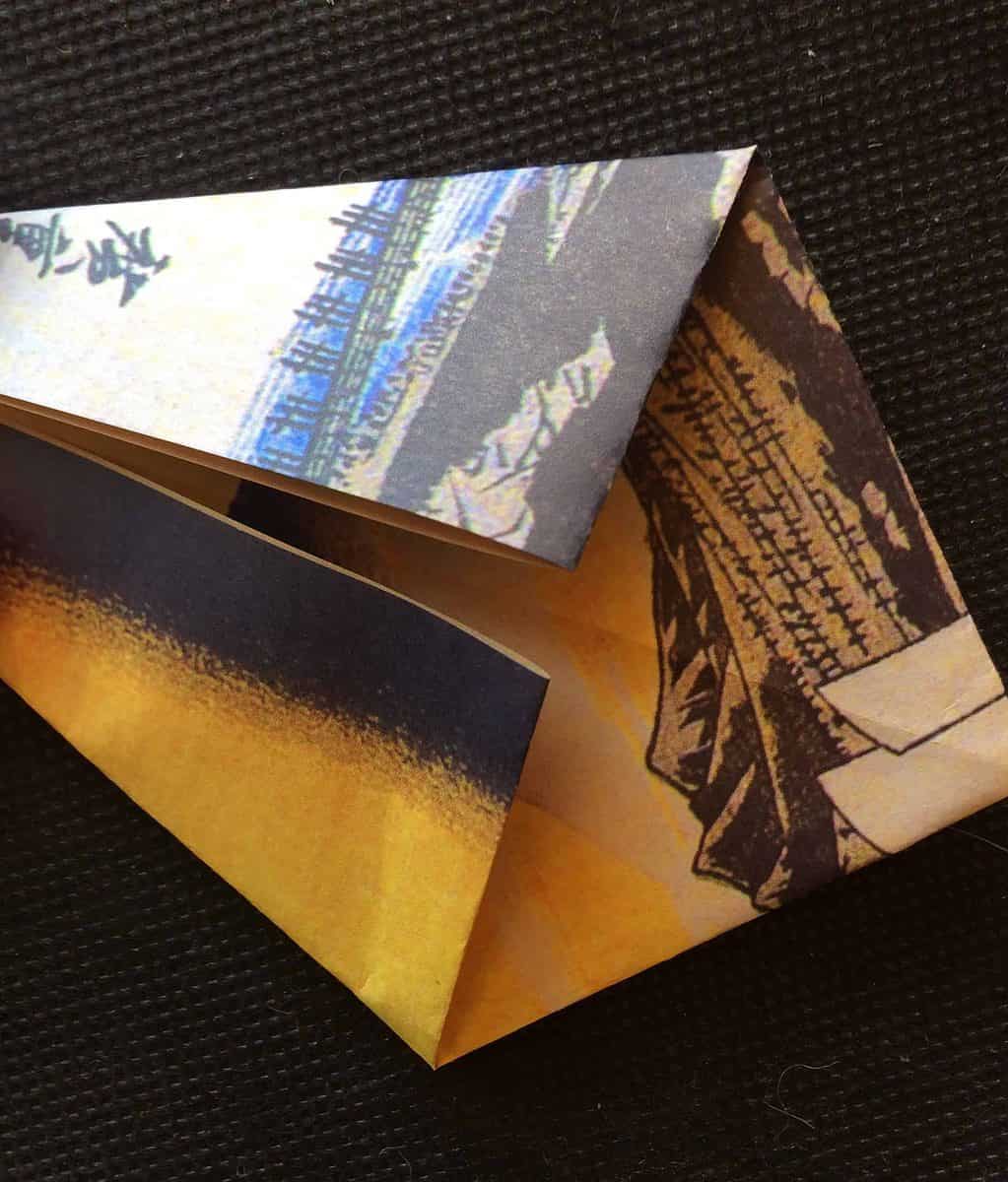

It was a few bright spots against white snow that stood out. Upon further inspection, the remains of two slightly ripped square papers appeared. They were adorned with Asian-inspired print on one side and a blanket cover of colour on the other. It was an image from the film Blade Runner that connected the paper’s purpose to that of the art of origami. These gems of a find soon ignited a fury of wings …

Origami (ori meaning “folding” and kami meaning “paper”) has an unclear origin. Although thought to have developed with the invention of paper, itself (according to origami scholar Hatori Koshiro), origami either originated with the Chinese, some 2000 years ago, and was then incorporated by Japanese culture during the Heian Period (ca. 800 CE), or developed in Japan around that time.

“We were not content to be victims. We refused to wait for an immediate fiery end or the slow poisoning of our world. We refused to sit idly in terror as the so-called great powers took us past nuclear dusk and brought us recklessly close to nuclear midnight. We rose up.”

(From activist Setsuko Thurlow’s 2017 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech)

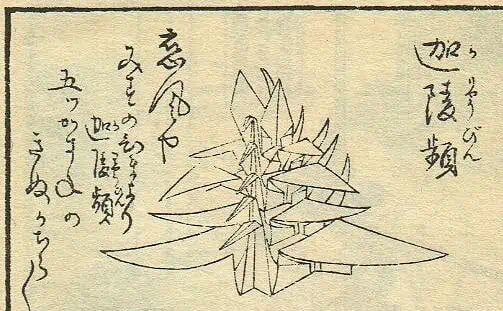

Hatori states that the first documented description of origami is found in a short poem by Ihara Saikaku, in 1680 (Rosei-ga yume-no cho-wa orisue or The butterflies in Rosei’s dream would be origami). Throughout the eras since its development, the art of origami has been used for both recreational and ceremonial purposes.

The oldest origami book appeared in 1797, entitled Sembazuru Orikata, by Akisato Rito. “Sembazuru” means one-thousand cranes. In Japanese culture, cranes are held in high regard and are believed to live for 1000 years as pair bonds that symbolize such qualities as longevity, happiness, health and peace. At that time “to fold” meant not a singular crane from one paper, but dozens of connected forms.

An offshoot of ceremonial origami arrived in Europe at some time during the thirteenth century when a replica of what appears to be a Ramma Zushiki (an origami boat) can be found in Tractatus de sphaera mundi (a medieval introduction to astronomy).

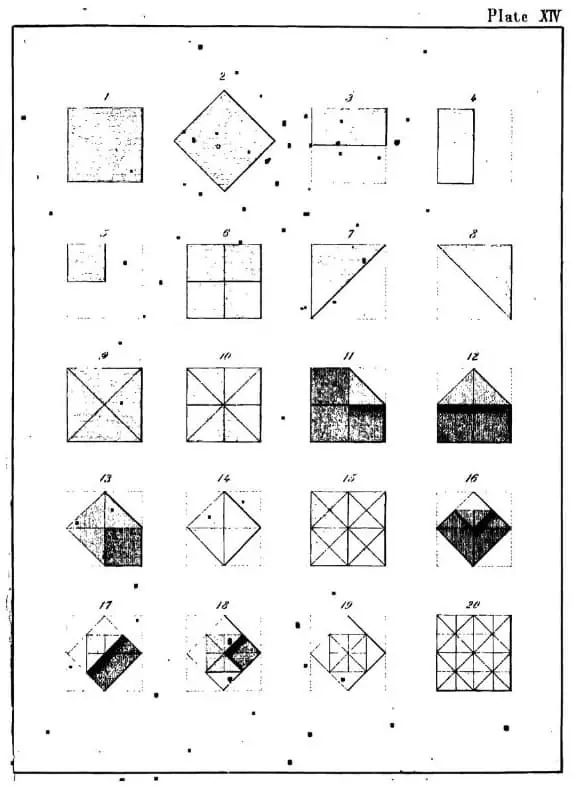

Later, during the nineteenth century, paper folding became a common practice in both Japan and Europe. By the mid-nineteenth century, Friedrich Fröbel of Germany established the first Kindergarten. Fröbel’s curriculum included three areas: forms of life, forms of beauty, and forms of knowledge, of which origami was categorized under all forms, viewed as elementary geometry, and was considered a valuable “occupation” for children.

According to scholar Koshiro, traditional origami from Japan had folding sequences that were passed down through the generations and that allowed for innovation among its practitioners. In comparison, the Modern Era includes designs that are considered intellectual property of a sole inventor.

Origami’s Modern Era is considered to have emerged out of cultural exchanges during more traditional times. It is considered a hybrid tradition of various cultures—an East-West fusion—mostly commonly known by its Japanese name.

The practice of folding paper has both mathematical appeal, as well as artistic merit: folds provide insight into complex phenomena involved in geometric shapes, while forming aesthetically appealing figures. Origami grandmaster Akira Yoshizawa is considered to have elevated the practice into a figurative or living art form. Yoshizawa considers origami to not only represent beautiful forms, but to be capable of expressing emotion.

The crane is considered the most classic of origami folds. The Japanese folkloric tradition of folding one-thousand cranes (senbazuru) is associated with a Confucian belief that one would live for a thousand years (or be granted one wish) if they completed the task.

In the aftermath of Hiroshima, a school girl named Sadako Sasaki adopted the project in the hopes of recovering from the effects of leukemia after nuclear radiation exposure. And while the story of Sadako is a tragic one, the trend spread. Since that time, the art of folding cranes has become a powerful symbol for peace, healing and reconciliation. At the Hiroshima Peace Memorial and Children’s Peace Monument, in Japan, and at such sites as within Manhattan, in the aftermath of 9/11, strings of colourful origami cranes are a common fixture.

During the pandemic, and in subsequent days, the folding of cranes has continued to be a means of expressing grief or hope for more health-filled days and/or a peaceful end to conflict. For some, it has become a habit almost as compulsive as that of media watching. If timed, to fold one crane would procure yet another update or breaking story on a news source such as CBC.

Much like the origami-inspired James Webb Telescope, if we were to peer six months into the future, some of us might contemplate what new mysteries could unfold … what might be learned about the past, future, and the nature of the universe itself?

Until that time, high-quality origami paper can be purchased locally at Mac’s Fireweed Books, online from Tuttle Publishing (www.tuttlepublishing.com), or found at specialty stores in major cities. And if cranes are not your interest, free folding instructions can be found, online, for monsters, animals and a variety of forms (Including Gaff’s unicorn from Blade Runner).