Yukon College mine-life-cycle researcher Dr. Guillaume Nielsen likes to find innovative solutions to problems. Sometimes those solutions even involve ingredients one might also spread on toast or use in holiday baking. Take Nielsen’s PhD project, for example, where he explored ways to remediate mine-impacted water in the North by using naturally occurring organisms. Through laboratory and pilot studies, he found that just like humans, water-cleaning microbes prefer a sweet, calorically dense treat—like molasses—when it’s cold outside.

It was the first research of its kind to be done in the North. Using his skills and knowledge to help preserve the environment is something close to Nielsen’s heart.

“Being an outdoor enthusiast, I love the Yukon wildness,” Nielsen said. “This is why the environment is such a huge focus of my work.”

Nielsen grew up in France, where his adventurous spirit found its spark within the pages of Jack London’s Call of the Wild. Then Nielsen left Europe for the wide-open spaces of Canada. After a few years in Quebec, Nielsen and his wife moved to the Yukon in 2013. They settled into a dream situation—a cabin with no running water and with 35 sled dogs for company.

In his new home, Nielsen began finishing his PhD while working through the Yukon Research Centre at Yukon College as an academic partner.

The College works closely with industry in its mine-life-cycle research projects to address northern specific challenges and opportunities. In this case, Nielsen’s project explored mine-water remediation, finding new ways of taking potentially harmful chemicals from water that’s been produced during mining processes—it’s what the industry calls “acid mine drainage” or AMD.

There are two ways to approach cleaning AMD: active treatments and passive treatments. Active treatments introduce new chemicals, such as lime, into the environment. For Nielsen, the goal is to find new or better passive treatments that rely on using living things already present in the environment.

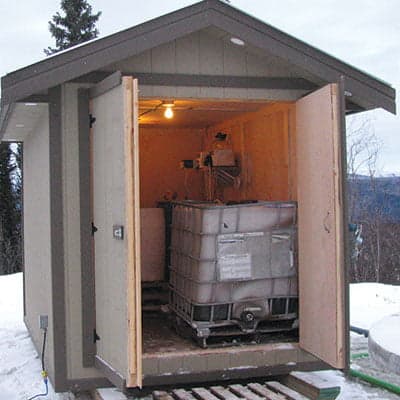

He started his exploration with a technology, usually used in places warmer than the Yukon, called a sulfate-reducing bioreactor, which relies on microbes to function. These naturally occurring organisms can take in heavy metal contaminants in liquids and render them harmless.

Instead of oxygen, these microscopic powerhouses use sulfate in their respiration chain.

“That’s good news,” Nielsen said. “Sulfate is one of the products we always find in acid mine drainage.”

Bacteria use sulfate and carbon to produce sulfide that combines with the heavy metals present in AMD—such as cadmium or zinc—to create solid material, which can be released without damaging the environment.

These bacteria have been proven in the South, but can they work the same way in the North? Nielsen wanted to find out whether cold affects the bacteria and, if it does, what is needed to keep them “happy.”

He started testing in the lab, then moved on to a pilot project where he found that, yes, the cold affects the bacteria, but giving them the right substances to “eat” can keep them working effectively. He experimented with giving them a number of different carbon sources, such as peat, methanol, ethanol, potato oil, even brewery residue, to find the best fit. As it turned out, they liked molasses mixed with methanol best.

“In the pilot study, we found 95.5 per cent removal of zinc and 96.3 per cent removal of cadmium after 90 days,” Nielsen said. “These were very promising results.”

His research involved invaluable partnerships with Alexco Environmental Group, contracted to remediate the historic Keno Hill Silver Mine District, and the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyak Dun.

“I think it was a win-win-win situation,” Nielsen said. “I believe that First Nation traditional knowledge needs to be involved and integrated into research projects.

“They learned from us, and we learned from them as well. I always see numbers, like discharge limits, while they are talking about things like caribou and moose, and whether they come back. It makes things very practical and real, and it’s a very good source of motivation.”

Nielsen finished his PhD in 2017, and his research paper has recently been accepted into the high-level peer-reviewed Water Research Journal. He has recently returned to work at the Yukon College as a research associate.

“This is something that I cannot wait to continue work on,” Nielsen said. “We have an amazing opportunity here in Yukon to develop expertise in passive treatment systems for mine waste water in cold climates. We are in the North, and we have the mine sites. It’s a very unique and exciting situation.”