Snow. It affects our lives in the North for half the year … but other than wiping it off the windshield of your car or shovelling it from your driveway, what do you really know about the dynamic and interesting snow?

Defining snow

Snow isn’t as I always imagined it would be. I grew up in Australia and my ideas were that it was going to be like the cotton-candy clouds or puffy marshmallows depicted on TV. Instead it’s cold, hard, wet and there’s lots of different types of snow—from sleet to perfect fluffy crystals. Erik Stevens gives us his definition in the following:

Solid crystals that condense out of a gaseous cloud at temperatures below the freezing point. Interestingly, this can apply to many other compounds besides water. For example, methane snow falls on Pluto (Pluto even has methane glaciers!), Carbon Dioxide snow falls on Mars; Sulfur snow falls on Io [Saturn’s moon}, etc. – Erik Stevens

Having lived in Revelstoke, B.C., the snow mecca of Canada; and in Whitehorse, a snow desert, I’ve come to learn my different snow types.

Basic types of snow

Rain: It makes you wet and it’s not cold enough to turn into ice crystals

Hail/sleet: It’s gotten colder and it’s like a teenager, unsure if it wants to rain or snow (so it’s something in-between)

Snowflakes: Those pretty, perfect little individual snowflakes that fall from the sky like something out of a fairy tale (everyone’s favourite type of snow)

To me, snow is three juxtaposing things. It is a scientifically fascinating material, it’s water, which we typically think of as the quintessential liquid but in its crystal form. It also has some magic substance that seems to draw out my inner child, it’s such a unique medium to interact with. Who doesn’t love to play in the fresh snow! At the same time, though, snow has the potential to be a destructive force, and snow avalanches have the power to harm and destroy. My relationship with snow is pretty complex. – Eirik Sharp

Snow has so many useful properties, no matter what stage of life it’s in, and it sometimes brings joy and sometimes brings frustration.

Snow is cool because …

It is usually soft: you can crash in it without hurting yourself!

It’s fun for gliding on

Snowball fights are fun

It’s bright (winter is dark)

Powder face shots (skiing, snowboarding, sledding)

Its solid volume is greater than its liquid volume (ice floats)

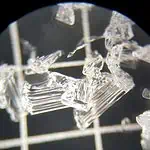

There are so many different crystals … it’s nature’s art

You can see animal tracks in it (Catherine Henry, paraphrased)

Why snow is so interesting

Every second, snow is changing; it is never the same at any point in time. It’s continually evolving based on the elements that transition it throughout its life, such as wind, sun and temperature.

“Snow crystals are in a constant state of flux, always changing, even after they’re on the ground. The crystals grow, shrink, change shape, become more or less dense and become stronger or weaker over time. This keeps us on our toes …” – Erik Stevens

Have you ever just let snow sit on a car or a house? What happens to it? It slowly starts to slide. Snow is extremely elastic, like a rubber band; it stretches and stretches until it breaks. As it also changes and adapts and morphs, it is replaced with more, or lost as we come into summer, but it’s never the same.

As a skier, snow allows me to interact with the landscape in a uniquely tangible way. As I travel through the mountains, I leave a signature with my feet. A well-chosen ski track, down an otherwise untouched, open mountain slope covered by a thick blanket of new powder snow, is one of the few ways people can enhance the beauty of nature. I think that is partly because, unlike so many of our other actions, it is completely impermanent, destined to be erased by the next snowfall. – Eirik Sharp

Snow is important

Snow means water and it determines why certain regions are plentiful and other are not in that resource. Climate and precipitation can affect how much snow there is and therefore how much water there is.

In a more pragmatics sense, snow has an important relationship with climate. It is highly reflective to incoming solar radiation; and this, combined with its insulating properties, means snow cover has a pronounced effect in cooling of the atmosphere through the winter. However, seasonal weather patterns also affect snow cover and snow properties. And measure of changes in snow cover are crucial to understand changes in local, and regional climatic regimes. – Eirik Sharp

In Queensland, Australia, many of us couldn’t remember a time without water restrictions. We had egg timers in our showers to restrict how much water was used because of dead front yards and the expense. In Canada’s northern, snowy environment, water flows freely and cheaply.

“Here on Earth, snowpack that builds in the mountains provides the sustainable source for the waters that allowed civilization to build and thrive. Because snowpack builds up over the winter and releases that water slowly throughout the spring and summer (which are often dry months), rivers continue to flow in reliable patterns, even during long, dry periods without rain. But most importantly, snow is fun.” – Erik Stevens

But snow doesn’t just mean water and its environmental benefits, it is also important for tourism. As winter activities become more popular, many count the days until they can ski (downhill and cross country), snowboard, sled and snowshoe.

Northern snow is unique

Having moved from the little ski town of Revelstoke, B.C., where one metre of snow falling overnight was a small dump day for skiing, it was a hard transition when you love skiing as much as I do. But what was even stranger to me was the type of snow here in the Yukon. It’s like sugar.

“The very low temperatures in the Yukon cause the snow crystals in clouds to form as small columns and plates, rather than the large, fluffy, feathery things called Dendrites that form in warmer, wetter clouds. The crystals just can’t grow as big and fluffy as they do closer to the freezing point. Also, the amount of moisture the air can hold decreases as the temperature gets colder. Once the temperature falls below about -20℃, there is too little moisture in the air for snowflakes to really form. This is largely the reason why the coldest regions on Earth are all deserts.” – Erik Stevens

“Dry snow” or low water content. Generally continues drying throughout the winter because low relative humidity (sublimation). Non-cohesive, facets, “sugary”, “bottomless.” Wind is a big factor because not many trees (alpine) – transport, slabs. The climate is too dry and cold for large accumulations. – Catherine Henry

Well, most obviously it [snow] sticks around for longer up here and so it is a bigger part of life. But I think changes in the patterns of snow are serving as a bell-weather for climate change in the North. Our winters are getting warmer, we seem to be getting less snow than in the past and our glaciers are receding at what seems an ever-increasing rate. – Eirik Sharp

Did You Know?

When it’s between 0℃ and -10℃, the snow underfoot melts slightly when you step on it and compress the crystals. This lubricates the friction and makes your footsteps quieter and more slippery. But when it’s colder than -10℃, that microscopic melting doesn’t happen, and the increased friction of the crystals smashing together causes a noticeable squeaking sound. It also increases traction on those snow-packed roads.

Thanks to my snow-nerd scientists who I met through my avalanche training and a weather station project in Kluane. Their lives revolve around snow and they couldn’t wait to “nerd-out” on the subject:

Erik Sharp is a self-professed snow nerd, avalanche expert and ski guide. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Math from UBC, a Master’s in Avalanche Mapping, through the University of Leeds, UK (distance ed.)

He is an ACMG, Association of Canadian Mountain Guide, a professional member of the Canadian Avalanche Association. He also teaches the Canadian Avalanche Association Industry Training Program, as well as a weather course level 1 and 2 curriculum.

Catherine Henry is a senior environmental scientist for Core Geoscience Services Inc. She holds a Bachelor’s degree in Atmospheric Science and Physics from McGill University and a Master’s in Environmental Sciences from Université du Québec à Montréal, and also has her CAA Avalanche Operations Level 1 certification.

Erik Stevens is a forecaster and director of the Haines Avalanche Center. He holds a Master’s degree in Remote Sensing, Earth and Space Sciences, with certificates in Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences and Oceanography. He holds his Level 3 certification from the American Institute for Avalanche Research and Education (AIARE), and his AIARE Avalanche Level II certification. He’s a professional member of the American Avalanche Association.