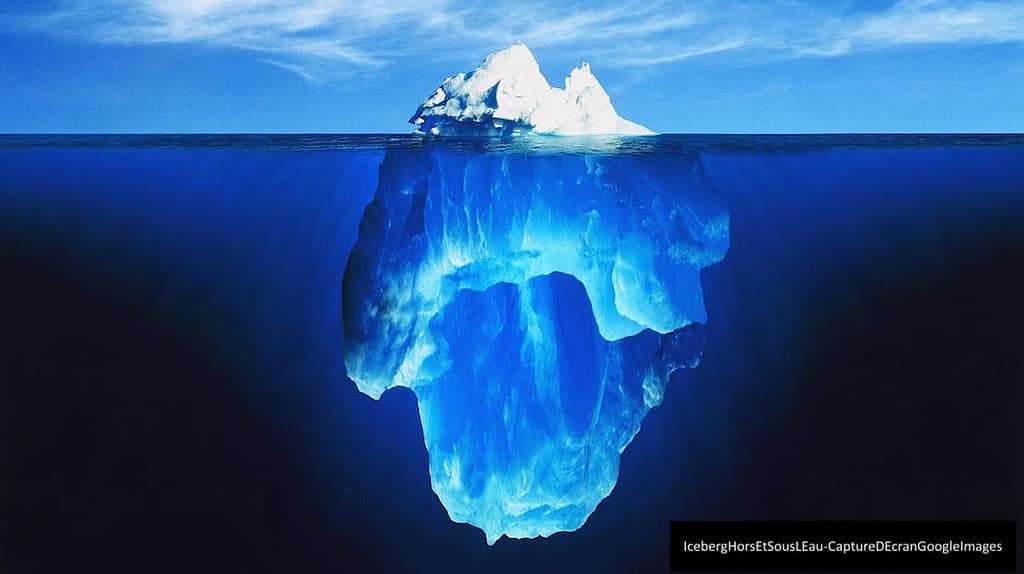

All specialists dealing with the subject of violence agree that the majority of people only recognize physical forms of aggression such as conjugal or affective violence. Like the tip of an iceberg, it takes the form that we know best since it is visible. However, with some exceptions, it is quite rare for physical conflict to be the first manifestation of violence. Generally speaking, violence develops gradually—bit by bit—and actually originates in more subtle ways. In this sense, we can flesh out an escalation of violence that I would like to briefly describe. The cycle of violence (for example, in its affective form) develops in four phases of varying

length and intensity (Walker, FL, 1977). For example, it can develop between romantic partners (affective violence) or at work (organizational violence). With time, the intensity of the violence increases and its consequences become more important.

Phase 1 – Accumulation

Tension develops as a result of a series of minor incidents. The aggressor creates tension and

the fearful partner feels threatened. This process generally causes the victim to lose their

temper and concentrate on the mood of the aggressor.

Phase 2 – Explosion

Like a bomb with a fuse lit during the initial accumulation phase, this phase is the explosion of violence, or rather of aggression. During this period, the aggressor gives the false impression of a loss of control, and the victim is in a state of panic while they try to make the source of their irritation disappear.

Phase 3 – Honeymoon

Indeed, we call this phase the “honeymoon.” The aggressor expresses regret, asks for forgiveness of the victim and makes plenty of promises—flowers and chocolate included. Alas, this phase of the cycle restores hope that the aggressor will change, and it encourages the victim to resume or continue a relationship. However, without help, the couple starts the recurring cycle of violence anew. Further, the honeymoon phase shortens as the cycle repeats itself … to the point of disappearing completely.

Phase 4 – “Yes, but it’s your fault.” (Justification)

The aggressor tries to avoid responsibility and argues, “Yes, but it’s your fault.” This process is the same in all couples, regardless of gender and orientation. This phase is an attempt to nullify

unhappy acts and to convince the victim that they are dramatizing, that they are crazy, that it’s

their fault and that they should not have provoked the aggressor’s rage. As a result, the victim is

led to believe that the violence will end when they modify their own behaviour. And the cycle

begins again, ad nauseam!

These are the four phases of the cycle of violence: accumulation, explosion, a lot of justification and, finally, a honeymoon. Unfortunately, this is an unending cycle unless the victim (or victims) try to protect themselves by asking for help to find a way out of this life-poisoning whirlwind.

My next article will define and categorize violence. These notions are beneficial throughout your life if ever you find yourself confronted, near or far, by violence. A list of useful resources available in the Yukon is included here.

Resources in the Yukon

Emergency

Whitehorse: 911

Communities: first 3 numbers and 5555

Help and Victim Services

Yukon and Northern B.C.: 1-800-563-0808

24/7 shelters (collect calls)

Carmacks 863-5918

Dawson 993-5086

Ross River 969-2722

Watson Lake 536-7233

Whitehorse 668-5733 / 633-7699 / 667-2693

Whitehorse Les EssentiElles 668-2636

Elder abuse: 1-800-661-0408 x3946

Residential school survivors:

867-667-2247 (collect)

Yukon Distress & Support Line: 1-844-533-3030

Child support and protection

Atlin 651-7511

Beaver Creek and Burwash Landing 634-2203

Carcross 821-2920

Carmacks 863-5800

Dawson 993-7890

Destruction Bay and Haines Junction 634-2203

Faro 994-2749

Mayo 996-2283

Old Crow 993-7890

Pelly 863-5800

Ross River 969-3200

Teslin 390-2588

Watson Lake 536-2232

Whitehorse 821-2920

Sources: The first pages of your Yukon and Northern British Columbia phone book.

The website: “Surviving in Yukon”