The sound of inflation bags wheeze in the morning as the packrafts slowly take form. The pile of monitoring gear is prepared to be loaded into the rafts. Today, Parks Canada staff will be collecting water quality samples of the Shadhäla Chù/Dezadeash River and wetland complex in Kluane National Park and Reserve. Once the first sample is taken, the clock starts. Water sampling in the North can be tricky; to get accurate results, our samples have to make their way to a lab in Vancouver to be analyzed within three days.

But even before we start sampling, our day is already interwoven with the story of water’s passage. Mornings are different for everyone, but likely, teeth are brushed, the shower runs, the toilet flushes, the kettle or coffee pot is filled, dishes are washed. According to 2017 data from Statistics Canada, the average daily residential use of water in the Yukon was 383 litres per person per day. Few of us think about where that water goes after using it.

In the Village of Haines Junction, the water makes the journey from the pipes of homes to the wastewater treatment facility located south of the village. After undergoing treatment, the water is discharged periodically to free up volume in the facility, returning to the natural system that crosses invisible boundaries of village land, settlement land and national park.

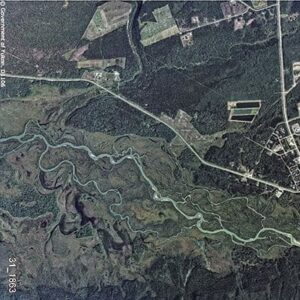

Water quality is an important component of the ecological integrity of freshwater ecosystems. Kluane National Park and Reserve is 22,000 square kilometres of mostly vast icefields and tall mountains, but also of boreal forest, alpine tundra, wide river valleys and wetlands. The Dezadeash River, which meanders across the traditional territory of Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, flows into the park, ultimately joining the Kaskawulsh River to form the Alsek, a designated Canadian Heritage River.

Wetlands are biologically diverse systems that enhance water quality and provide habitat and sanctuary for species such as wood frogs and migratory birds. The Dezadeash wetlands span across an estimated 30 square kilometres of channels large and small, with water seeping across waves of grass. Swans and other migratory birds can be typically found using this landscape as a rest stop or refuge before pushing further north, while others call it home for the summer.

Parks Canada collects water samples of this river system at six sites, twice per season, once prior to discharge from the water treatment facility to gain a baseline of that year, and a second time after discharge to see the possible influences of the treated effluent. Monitoring yields information including temperature, pH, total and dissolved metals, and nutrient levels.

To determine the best spots to sample, we turned to an unexpected helper. Artificial sweeteners can be found in many products we consume (even in most toothpastes) and can be detected in very low concentrations. Since they don’t occur naturally, artificial sweeteners act as a unique tracer, showing us how the discharge moves through the wetlands and helping to inform sampling locations.

Results from the water sampling are shared with partnering organizations to ensure that a high standard of water quality is maintained. Parks Canada works with the Village of Haines Junction, Environment Yukon, Environment and Climate Change Canada, Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, and researchers from the University of Waterloo and Western University in monitoring the overall health of the wetlands and greater Dezadeash River.

The methodical rhythm of plunging paddles moves us closer to the next site as we follow the path of the water. The continual hum of nature is interrupted by the flight of two large trumpeter swans honking at our presence. With the final squeal of the Nalgene lid, the last sample bottle is closed. Ice packs are jammed into the cooler, as the water is prepped to make its last leg in its sampling journey.

The methodical rhythm of plunging paddles moves us closer to the next site as we follow the path of the water. The continual hum of nature is interrupted by the flight of two large trumpeter swans honking at our presence. With the final squeal of the Nalgene lid, the last sample bottle is closed. Ice packs are jammed into the cooler, as the water is prepped to make its last leg in its sampling journey.

This evening, the water will travel to Whitehorse, and by tomorrow morning will be taking flight, travelling in ways that we are currently unable to, while the remaining river water runs across the B.C. and U.S. borders, passing glacier after glacier, eventually consumed by the Gulf of Alaska. The only rule that water seems to obey is that of gravity, as it ripples and eddies, ignoring our boundaries and our deadlines.