Eighteen years ago three sheep hunters named Bill Hanlon, Warren Ward and Mike Roche happened upon the body of a young Indigenous man while crossing a glacier in Tatshenshini-Alsek Park on Champagne and Aishihik First Nations traditional territory in northern B.C. Unbeknownst to the hunters, they had discovered the oldest natural mummified body unearthed to date in North America. The man was frozen in place during the Little Ice Age in the summertime, c.1450–1700 AD.

“It was my life for three months working day and night,” said Diane Strand, director of community wellness at the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, who was working as a heritage resource officer with CAFN during the project.

The Tatshenshini-Alsek Park is under a co-management agreement between CAFN and the B.C. government, in which CAFN has sole responsibility over heritage matters. “We had stewardship over him (the Long Ago Person Found). We knew that he was probably one of us,” she said.

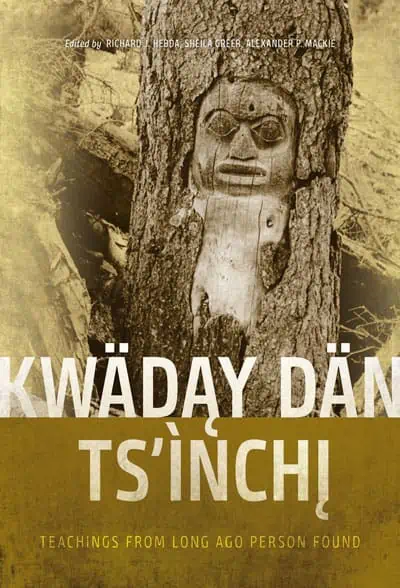

After consulting with elders in the community it was decided that the scientists at the Royal B.C. museum would be allowed to study the remains of the Kwädąy Dän Ts’ìnchį – which means “Long Ago Person Found” in Southern Tutchone – for one year. After that he would be given a traditional cremation on the site where he was found and a potlatch was to be held in his honour.

It was important to Strand that the body be treated in a respectful way during the study. “This was someone’s son and his body was our responsibility. It was about honouring him and his family in the proper way,” she said.

With that in mind CAFN also conducted DNA tests with 241 volunteers and they were able to confirm 17 people related to the man though the maternal line, 15 of whom identified with the Wolf clan. (Children are born into the mother’s clan under the matrilineal system common among Yukon, B.C. and Alaska First Nations). The current day relations are roughly even split between coastal and inland dwellers.

The man was likely a mix of coastal and interior Yukon, B.C. and Alaska First Nations. This would reflect trade routes between communities at the time. It would also make sense based on his DNA, diet and the belongings that he carried with him at the time of death.

This hypothesis would also coincide with the location where he was found – along what Strand said was once a popular glacial trade route between coastal and inland communities.

Strand said that while the Kwädąy Dän Ts’ìnchį was an important discovery for the scientific community, for Indigenous people it was more than that. She said that the entire process from the discovery to his cremation ceremony helped her connect with her own spirituality on a deeper level. “It’s who we are. It’s our ancestry. It’s given pride to our future generations and our kids.’’

The book will be introduced in the Yukon during the Haines Junction Mountain Festival, which takes place December 8 to 10 in Dakwäkäda (Haines Junction). The Long Ago Person Found’s belongings will also be on display at the Da Kų Cultural Centre in Haines Junction.