There’s a quiet old guy in the town I’m living in named Joel. Joel’s been a trapper all his life.

From Joel, I’ve learned that most short in-between words in English are superfluous, given a bit of context.

He can say three simple words and I’ll think I’ve never heard those sounds together before, but if I pause to consider what he’s probably thinking about (caribou, getting wood, the trail) as soon as I’ve guessed it, his words become obvious.

It’s like magic—where the conjunctive should be, there’s clarity!

I’ve had the pleasure of travelling with Joel to his camp on the Old Crow Flats.

The flats is a grand system of some 2,500 lakes and a long, long winding river. The lakes are surrounded by a ring of mountains, with a small gap to the south where the Crow River flows into the Porcupine at the town of Old Crow.

When Joel was young, all the families in town would head out to the flats in March to trap muskrat. They’d spread out to about 30 camps over the 6,000 square kilometers of shallow lakes and wetland.

They would tether five to eight fluffy dogs to each toboggan and load them with gear. The dogs tinkled with bells as they ran—you could hear them from miles away.

The wood sleds and leather harnesses were made from scratch and elaborately decorated.

The dogs were big, tough, and reliable. They had been with the Gwich’in since before white men, “since Asian days”.

Joel once took the dog sled to his trapping camp on Old Crow Flats. Now he rides a snowmobile

Muskrat flourish in the myriad of shallow lakes that don’t freeze to the bottom. In winter, they build little grassy lodges over their air holes called “pushups”. If you mark the pushups with sticks in November, you can easily find them under the snow in the spring and set traps.

Muskrat season is often a time when caribou haven’t been around for a while. The people would live off of their remaining dry meat, and hunt tasty little critters like rabbit, ptarmigan, porcupine, beaver and gopher. They’d dry out the extra muskrat carcasses to save for dog food.

Joel says there used to be more little animals, as well as freshwater fish, and ducks during spring migration. Though animal populations cycle, he says they’ve been down for a long time, except for moose and swan.

The vegetation on the flats has changed, too. The willow are bigger, and there are more spruce growing everywhere.

As for the weather, he used to be able to trap muskrat at their air holes until the first of June. Now the weather is too unreliable so the ice isn’t safe. He says they relied on regular seasonal changes in weather that just aren’t predictable any more.

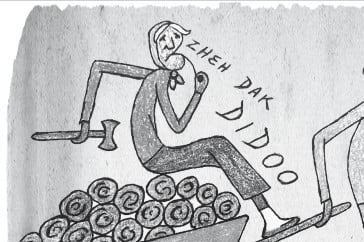

As night shortened to nothing and the warm sun melted the snow from the wetlands, the families would move down to the river. They cut fresh spruce and split the timbers with an axe to build rowboat frames. The boats were 24 feet long and five feet wide, and wrapped in heavy canvas.

By June 15, the river was free of ice. The families would each skid their new boat to the shore, flip it into the water, and fill it with all their gear, skins, dry meat and muskrat carcasses, toboggan, dogs, and the whole family.

The boats highest on the river would start down first and meet up with the others as they moved along. Part way, they’d meet the guy with a 10hp outboard on his canvas boat. He’d push the flotilla the rest of the way down the winding, steep banked river, another 15 hours back to town.

At the time, there was only one trader in Old Crow. If they needed food or supplies to go trap, the store gave it to them. When they came back with furs, they gave them to the store. The trader kept track of the accounts.

No one saw the price list for furs. The only thing they used money for was to order fancier clothes from the catalogue companies.

In the ’60s, things began to change. “Fresh food” from outside became available for the first time.

In the late ’60s, the canvas boats were replaced by wooden boats with bigger motors that came up from town after breakup to pick everyone up. People also began to use skidoos instead of dogs.

The new machines were fast and powerful—a whole new age of convenience—but they had lingering costs and reliability issues. Whereas people and dogs can be powered on dry meat and fish, machines need gasoline and parts that can’t be made in town.

These things require money. In order to get money, people gradually began to work for wages. Jobs took up more of their time while machines allowed quicker trips onto the land.

Today there are only about four camps used in muskrat season on the flats. The other camps are still there, with high caches full of weathered relics from the old life, waiting for someone to brush the snow off and start again.

Joel says young people now prefer jobs and regular pay to the independent lifestyle of the trapper. He hopes the ones who are interested learn well and keep the tradition going.

Joel likes the trapping life. He likes being out there.

He uses a snow machine and a motor boat now, and goes out for days or weeks instead of months at a time. Still, he remembers what it was like to spend most of his time out of town, to be vitally connected to the animals and the land.

“Now we’re tourists,” he says.