If there is anybody out there who recognizes what is in these pictures, please step forward.

Recently, I found myself looking more intensively at lichens and mosses. As there are no blooming wildflowers in the midst of winter and as there happened to be very little snow in December 2018, they caught my interest. Lichens and mosses are beautiful enough in themselves, but I like to know their names and, as it turns out, I can’t find anybody who knows more than the basics. The basics would be something like, “well this is moss, and this is a lichen, and then there is reindeer moss, which really is a lichen called cladonia.

If your knowledge goes beyond that, it would be of great help. And if you are a kid who likes to study biology, oh, I would love it if you want to study to be a bryologist (mosses and liverworts) or a lichenologist, as there are none that I know of in the Yukon.

I talked to Bruce Bennett, with the Yukon Conservation Data Centre (CDC). At the moment, Denny Bohmer, also at the CDC, is updating the CDC list of all lichens reported to occur in the Yukon (not that there is necessarily anybody around to recognize them). Experts in the past have collected lichens and DNA tested them. Bennett also told me there is a research project at Duke University in North Carolina to look at the genetics and DNA of peltigera that grow here in the Yukon. Peltigera is a pelt lichen. Pelt lichen might be important for caribou. It is known that caribou eat caribou moss, which are lichen in the cladonia family. Bennett suggested that pelt lichen might also be important to their diet, as it apparently has a higher protein content.

When we, as Yukoners, want to know more about our lichen, more than they already know at Environment Yukon, there is no local expert to turn to. There are some bryologists knowledgeable in Yukon species (I think there are 800 known mosses here), but they are mainly experts outside of the territory. For example, Dr. Terry McIntosh, a professor at the University of British Columbia who specializes in bryophytes and arid land vascular plants, has been up here at least five seasons to look at mosses.

A man like McIntosh is invaluable because studying from books or computers only goes so far. I can read about a certain plant many times, or study it for hours, but when someone points and tells me what it is, learning happens in an instant. I now might be able to recognize that plant when I see it again. For example, it was Bohmer, by means of iNaturalist.ca, who explained to me what grows underneath the spruce trees around my house. The thick carpet of moss, with its reddish spine and feathery green, is called Pleurozium schreberi.

And when one knows what is normally out there, only then can one recognize when something is different, or new. For example, I bet the Yukon has a lot of unknown species. But where to start? The CDC does have many lists, plant lists, animal lists, and lists for different areas. All are accessible to the public if you ask.

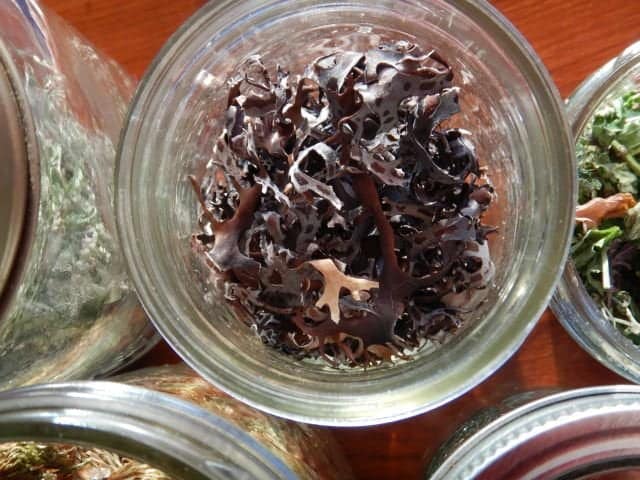

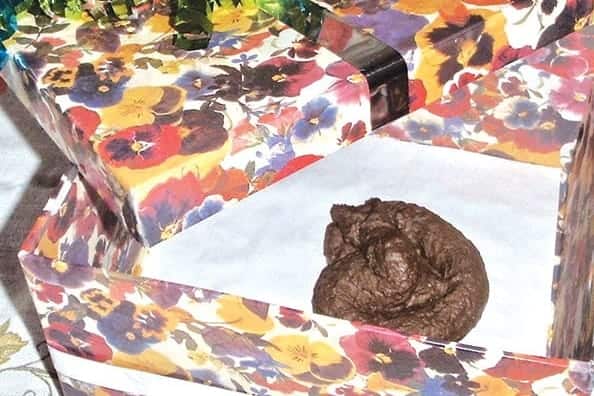

What I am also always interested in is the edibility of plants. I already know some lichen are edible and I have a jar of usnea, the beard lichen that hangs from tree branches. But I forgot what it is for. Walking to the kitchen now, toward a shelf full of jars of wild herbs that I collected and dried, I take some Masonhalea richardsonii and chew on it. Mmmm, delicious. An acquired taste though.