SKULLS

As per the Museum of Natural and Cultural History in Eugene, Oregon, the skull is “a framework of bone or cartilage enclosing the brain of a vertebrate” and is “part of the skeleton of a person or animal.”

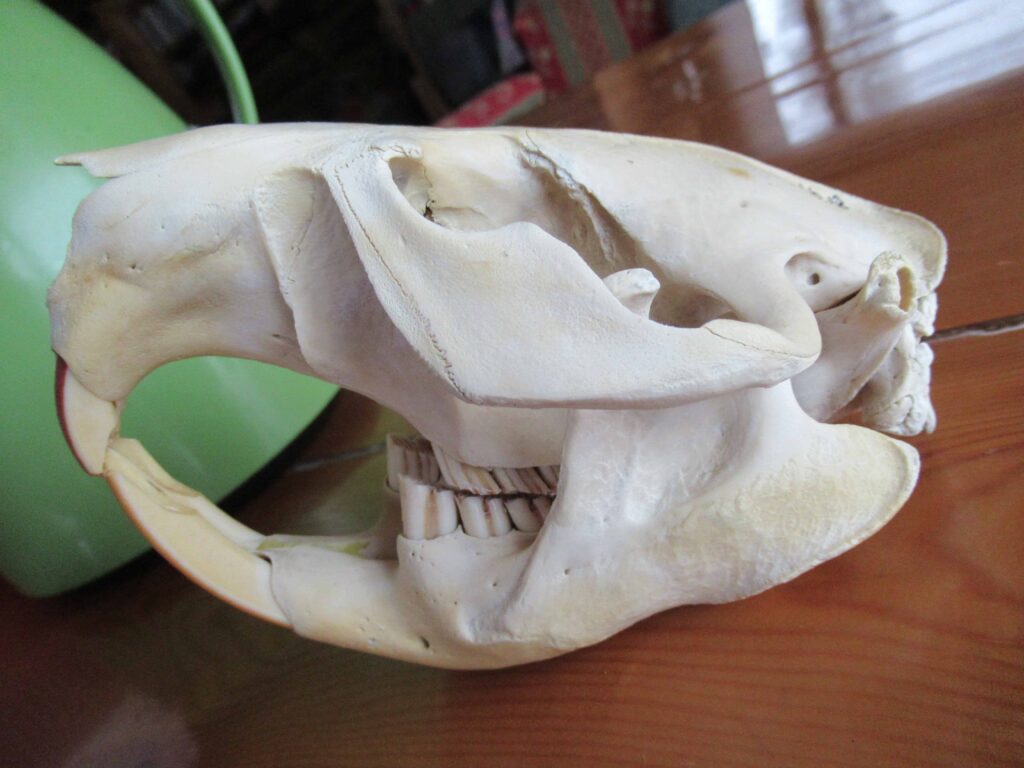

Now, say you find a skull already nearly stripped of flesh and you want to try to identify what animal it was. A key feature is the number and description of teeth. Long, dagger-like canine teeth will conclude that it is a predator like a wolf, so it can catch, hold and puncture an animal. A wolf is classified as a carnivore, but like the grizzly, I know they will also eat berries, so they are also omnivores.

Predator skulls are connected tightly, with big strong muscles, in order to bite and hold. We have caught a few wolverines that had porcupine quills in their noses, mouths and under their hides. An amazing feature of the wolverine is that often I am not able to separate the cranium from the mandible (the upper from the lower part of the skull), and that’s why they can take a grizzly’s moose kill and can crack the moose’s leg bones quite easily. Moose, beaver and muskrat, all have totally different teeth in the back as they eat plants and the upper and lower part of their skull needs space to chew from side to side.

If you know what to look for, then you’ll be able to guess what an animal ate and if it used smell or sight or hearing in order to find food or to avoid being eaten. Mice, for instance, have eyes on opposite sides of the skull: this gives them a wider view of the field and much more time for scurrying away when a hawk shoots down from out of the sky. Owls, then, as predators, have big eye sockets and overlapping sight (creating a 3-D effect) so that they can hunt at night and perceive depth and distances better.

BEETLES

How would you go about cleaning a skull? Enter the Dermestid beetles. They’re not in the same category as piraňhas, so they will not eat living flesh. Dermestid beetles won’t even bite you; they’re helping nature to recycle any dead and decaying animals. So if you feel your offspring might develop into an anthropologist, buy your little one a few hundred “pet” beetles and watch as they become fascinated by those critters and, at the same time, see the transformation of your moose head from a crawling beetle infestation to a clean and white skull. To clean a deer skull in a few days, you’ll need an established colony of about 1,000 or more beetles. But make sure they can’t escape from their cage, because then, if hungry enough, they will not say “no” to your carpets, rugs, wool, cotton, furs, feathers or paper. Your beetles won’t take kindly to freezing, so make sure they’re always warm. They’re most active at 80 F (26.6 C). If you can’t offer them meat for a few days, that’ll be okay; they’ll eat dry dog food.

Who else uses Dermestid beetles?

Museums, anthropologists and teachers will happily employ their beetles’ eagerness to clean any type of skull or bone. Forensics in law enforcement and crime investigations have started using them as well. Most taxidermists will rely on the little buggers, as those insects will go into the tiniest crevasses and won’t break anything inside a skull—not even the smallest bone structures (imagine trying to clean a squirrel, ermine or even a fragile bird skull!).

Go to the University of Arizona, Cooperative Extension webpage (extension.arizona.edu), to read up on how to properly and safely clean a skull by hand.

Q&A (Environment Yukon):

Q1: I know that I have to bring in my grizzly skull. Which tooth are you pulling, and can I get the skull back?

When a grizzly or black bear skull from a harvested bear is brought into Department of Environment offices, a tooth is pulled so we can learn more about the age structure of harvested bears in the Yukon.

- We also look at ages of bears that are killed in defence of life and property or submitted for some other reason, such as an unknown cause of death. Usually, one of the premolars is pulled from the skull for aging.

- The premolars to collect are located just behind the canines on the upper jaw.

- These types of teeth are the most useful for getting an accurate age. The tooth taken for aging is destroyed in the process, but the remaining skull is intact and can be returned to the submitter.

Q2: If I find a dead animal on the road or in the bush, what do I do in order to be able to keep it?

According to Linea Volkering, the Communications Analyst at Environment Yukon, Communications, if you find a dead wild animal in the Yukon, please report it to conservation officers. To possess any part of a wildlife carcass that you’ve found in the field, you must first bring it to a Department of Environment office and ask for a permit to possess wildlife found by chance.

- Environment officials are interested in determining the cause of the mortality.

- A conservation officer will ask you a few questions and may issue a permit depending on the circumstances and if possession of the wildlife is permitted under the Wildlife Act.

- However, they cannot issue permits for certain species protected by federal legislation.

You don’t need a permit to keep a naturally shed moose, caribou, elk or deer antler, as long as the burr at its base is intact. In some cases, when you bring in the carcass, you may not be able to keep it because of concern for disease or if the carcass is needed for other projects. However, depending on the animal species and the part of the carcass you are interested in having (such as the skull or hide), we can sometimes arrange to collect necessary samples and return the carcass to you.

There are some samples that are required for licensed hunters to submit from harvested species, such as heads from grizzly and black bears, and these can be returned to the submitter. In other cases, such as projects we have with wolverines and lynx, trappers can bring in carcasses of these species from their trapline so that we can use samples from them for a variety of projects. When found, dead wildlife are submitted and we may use them for a range of projects, depending on the species. For example, when dead birds are submitted, we collect samples to test for avian influenza. We may collect samples from other species, such as bears and wolverines, to look for parasites. In the case of foxes and bats, we may use samples from these species for rabies virus surveillance. If dead wildlife are submitted with an unknown cause of death, we perform a post-mortem examination on the animal, and the carcass is not suitable to be returned to the submitter.

Author’s Note: Make sure you wear rubber gloves or another proper barrier when handling found animals.

For information about reporting harvest results, including biological submissions, visit yukon.ca/en/report-harvest-results.

If you notice abnormalities in harvested animals or find dead wildlife, you can submit samples to the Animal Health Unit. Contact the wildlife veterinarian to let us know what you found (email [email protected] or call 867-667-5600) or bring the sample or carcass to a Department of Environment office.

Where in Whitehorse can I see skulls on display?

Just last spring (2023), the Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre remodelled their front hall; they now have a skull wall. McBride Museum has a few skulls and furs on display and, of course, many taxidermied animals. Yukon University has a skull display in their Science Hallway in A-Wing.

Sonja Seeber, Yukon Trapper