At this time last year, residents of Telegraph Creek and area were still displaced by forest fires that ravaged their land. Dozens of homes and buildings were destroyed and it was not until November that people started to return. Those fires started because of lighting, but in recent geological times fire reigned not from above, but below, in the form of extensive volcanic activity that affected the Tahltan people.

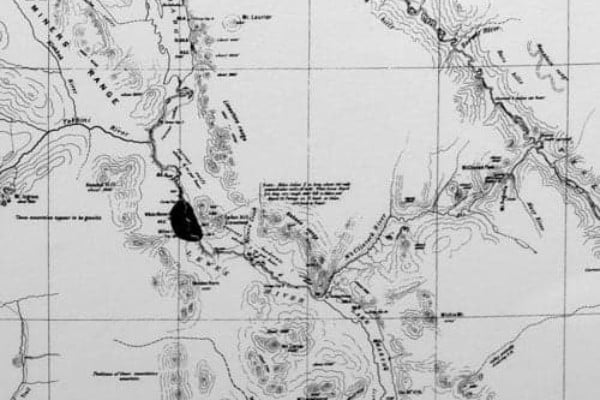

The area around Telegraph Creek is part of the northern cordillera volcanic province. This belt stretches from Stewart, B.C., in the south to the Alaska border near Dawson City. It first became active 20-million years ago. Basalt from these eruptions can be seen around Atlin, Miles Canyon, Fort Selkirk, and Sixty Mile River in the Yukon, but by far the largest and most spectacular were centered in the Stikine River area of British Columbia.

To the north of Telegraph Creek is Level Mountain covering over 2,400 square kilometres in area. The mountain is what is known as a shield volcano, like Mauna Loa in Hawaii. It is a low-profile, relatively gently sloping mountain made of a series of basalt lava flows totalling 1,000 metres thick. The volcano started erupting 15-million years ago and ended about 2.5-million years ago. Over 20 different eruption centres have been identified on the mountain.

On a clear day, the best way to see Level Mountain is from 35,000 feet on the port side of the Air North flight to Vancouver. Look for it 25 to 30 minutes after takeoff. South of the Stikine River is the Mt. Edziza volcanic complex. Not as big in area as Level Mountain, but it not only had basalt lava flows, but also explosive eruptions of rock and ash, geysers, hot springs, eruptions under glaciers and sulphurous gas vents. The terrain is a series of rugged peaks, cinder cones, and lava flow plateaus. Activity at Mt. Edziza began about 11-million years ago. Recent eruptions include 1,300-year-old cinder cones. There is evidence of ash layers that may be only a few hundred years old.

The volcanic activity is suspected to have been triggered by a change in the relative motion between the North American and Pacific tectonic plates. The two are in contact with each other about 100 kilometres west of Telegraph Creek. The colliding plates tore the crust, allowing magma to come to surface through the fractures.

The region became a provincial park in 1972, but the first humans in the area arrived around 10,000 years ago. The Tahltan peoples established inland along the Stikine River and the Tlingit on the coast in the Wrangell area. Both groups utilized the rich salmon resource along the Stikine and its tributaries.

Another valuable resource in the area was obsidian. Obsidian, also known as volcanic glass is a rock that is non-crystalline. That means it cooled so quickly the molten rock did not have time to crystallize, it just turned to glass. Obsidian is hard and brittle, with a fracture pattern known as conchoidal. These circular fractures form thin, sharp, hard surfaces ideal for cutting or making weapon tips. Most of the obsidian from the Edziza area is black to grey, but it can also be green, blue, red, brown, or even mottled.

Vera Asp, Tahltan name Chaudaquock, in her 2004 Simon Fraser University Masters thesis describes the Tahltan as “leaders in the trade of obsidian.” Mt. Edziza obsidian has been found in Haida Gwaii, Yukon, Alaska, and as far east as Alberta. The best source is found 20 kilometres south of the main peak at Edziza, near Raspberry Pass. This pass is a major east-west trending route through the mountains and has been used for thousands of years.

Edziza got its name from a Tahltan word Ah deeth Tha, meaning “ash and sand mountain.” Volcanic activity in the area is in the oral histories of the Tahltan such as the need to move camps quickly due to eruptions. Salmon runs would have been altered by lava flows blocking streams and rivers. A 1984 Simon Fraser University Publication named “Glass and Ice” by K.R. Fladmark describes the archaeology of Mt. Edziza. It describes a Tahltan legend of giant supernatural toads that lived high in the mountains. One was named E’dista that lived part underground and part underwater. Its breath would come through cracks and holes in the rocks. It was also associated with spreading fire over water.

Lava flows from both Level Mountain and the Edziza area were quite extensive and often flowed downhill into existing river valleys. Some reached as far as the Stikine River. The area where the Stikine has cut through the recent lavas is known as the Grand Canyon of the Stikine. Over 16 kilometres long, the canyon has walls that can be vertical cliffs measuring over 400 metres high. The river can narrow to as little as 20 metres. The Stikine is known as one of the last great wilderness rivers in the world.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, BC Hydro had other designs on the river. They had plans for several dams. One proposed dam, known as Site Zed, would have been 270 metres or about 80 stories tall. The Grand Canyon would have been completely flooded. The traditional way of life for area residents would have been altered forever. Their protests as well as poor economics at the time killed the project.

Another interesting feature in the area involves rocks, though this one is human-made. There are a number of rock cairns that occur in the alpine areas adjacent to the Stikine River 50 kilometres downstream of Telegraph Creek, mainly around the Scud River. These cairns are one to two metres in diameter and height. Quite often there are three together in a line, possibly indicating direction. The age of these is hard to determine. Scientists have tried using estimates of lichen growth on the north side of these cairns. It has been speculated they may be related to where the Tahltan and Tlingit met to trade goods.

If you have never been to Telegraph Creek, plan to on your next trip along the Stewart-Cassiar Highway. The geological features created by the volcanism in the area are spectacular and many are visible right along the road. It is about a 110-kilometre trip from Dease Lake. The road follows the ancient trail established by the Tahltan, which was upgraded to a pack trail by the B.C. Government as early as 1874.

It is a good road, but I would not take your new Ferrari or your Gus the Bus-sized RV down the road, as it can be quite narrow in places with sharp corners. Last summer’s fires will have had an effect on the road and hillsides nearby, so drive slowly and enjoy the views. The first half of the trip occurs on a low plateau of older volcanic and sedimentary rocks. About 60 kilometres in you can see Mt. Edziza in the distance to the southwest. At 75 kilometres you begin your descent into the Stikine Valley at the Tuya River.

Look for the different basalt lava flows stacked on top of each other along the valley sides. Some spots you can see flows on top of gravel from old river bottoms. Just downstream of Tahltan Village, right where the Stikine comes by, up high you can see an old river valley filled with radiating columnar joints The designs made by the cooled lava are amazing all around you, it is a magical place.