Twenty-six years after it was first proposed by Pierre Berton, in 1997, and 19 years after it was officially submitted by Canada, Tr’ondëk-Klondike, as the nomination came to be known, has achieved World Heritage status, having been officially inscribed at the UNESCO World Heritage Convention in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on September 17, 2023.

It’s been a long journey since that headline in the Klondike Sun and the Whitehorse Star, in 1997, proclaimed “Berton Proposes Dawson for World Heritage Site Status.”

This wasn’t the first time it had been suggested, but it was the beginning of a process that led to the following entry on the UNESCO website on Sept. 17.

The UNESCO website announcement (whc.unesco.org/en/list/1564) was concise and to the point.

“Tr’ondëk-Klondike

“Located along the Yukon River in the sub-arctic region of Northwest Canada, Tr’ondëk-Klondike lies within the homeland of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation. It contains archaeological and historic sources that reflect Indigenous people’s adaptation to unprecedented changes caused by the Klondike Gold Rush at the end of the 19th century. The series illustrates different aspects of the colonization of this area, including sites of exchange between the Indigenous population and the colonists, and sites demonstrating Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in’s adaptations to colonial presence.”

Parks Canada went into more detail on its website (parks.canada.ca):

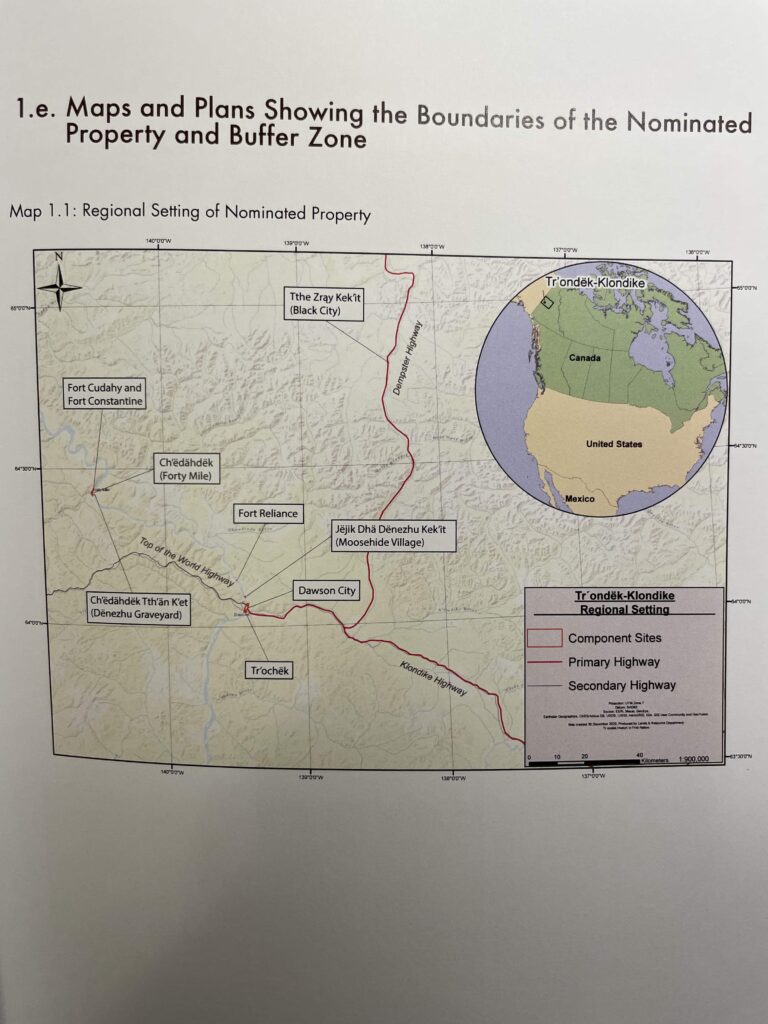

“Tr’ondëk-Klondike World Heritage site is a serial property comprised of eight distinct heritage locations: Fort Reliance; Ch’ëdähdëk (Forty Mile); Ch’ëdähdëk Tth’än K’et (Dënezhu Graveyard); Fort Cudahy and Fort Constantine; Tr’ochëk; Dawson City; Jëjik Dhä Dënezhu Kek’it (Moosehide Village); and Jëjik Dhä Tthe Zra’y Kek’it (Black City). These sites collectively total 334 hectares of land and encompass component sites along parts of the Yukon River and the Blackstone River.

“The unique cultural makeup of the region is the product of the coexistence of Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in and settlers over the last century and a half. The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in experience and adaptation to European settler colonialism marked the landscape with distinct cultural heritage attributes that remain to this day.”

This is a distinctly different site than the Gold Rush commemoration that Berton and his nominating partner, Pierre Dalibard, had in mind when they proposed this during the Gold Rush Centennial years (1996–98). Berton, of course, spent his pre-teen years in Dawson and wrote the Governor General’s Award winning Klondike: The Last Great Gold Rush, 1896–1899. He continued to write about the area until the last of his 50 adult and 23 children’s books.

Dalibard had worked for Parks Canada when the Klondike National Historic Site was created back in the 1960s. He also went on later to sit on the UNESCO board (ICOMOS — International Council on Monuments and Sites) that governs World Heritage Site selection.

The Parks’ press release* (parks.canada.ca) explained some of the process:

“During yesterday’s proceedings at the 45th session of the World Heritage Committee in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Tr’ondëk-Klondike, located in the homeland of Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in in northwestern Canada, was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List.

“Led by the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Government and the Tr’ondëk-Klondike World Heritage Site Advisory Committee, with support from the Government of Yukon, the City of Dawson, the Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency (CanNor), and Parks Canada, Tr’ondëk-Klondike tells the story of Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in’s experiences and responses to the startlingly rapid expansion of colonialism in their homeland between 1874 and 1908. Archaeological and historical evidence denotes timelines of both Indigenous and settler occupation of important sites throughout the region and together are a comprehensive record of the events that transformed the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in way of life.”

An earlier version of the proposal had attempted to include the goldfields, while specifically allowing the continuation of current and future mining activity. The branch of UNESCO that advises on conservation efforts—IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature)—raised objections to this, and when it was clear that submission would not be accepted, it was withdrawn and a revised submission was created which did not include active mining areas and which refocused on the Indigenous experience.

Disclosure: This reporter broke this story in 1997, after interviews with the original proponents, and has been an active member of the Tr’ondëk-Klondike World Heritage Site Advisory Committee (TKWHS) since its inception. A search of the WUY website will reveal several articles written during the first phase of this process.*License for use of source: whc.unesco.org/en/licenses/6