Getting to know the waterways along the Robert Campbell Highway

“I remember when we canoed the Pelly River in our handmade birchbark canoe, back in 2001,” Natasha reminisced as she looked across the river’s glistening surface from the grassy shoreline. “We had to portage just up ahead, around the Hoole Canyon. Imagine that … fourteen people carrying a sopping-wet birchbark canoe and gear over nearly two kilometres!”

I chuckled at the mental image while leaning over the riverbank and dangling a thermometer into the Pelly River, just upriver from its confluence with the Hoole River. “That sounds like something!” (I pulled the thermometer out of the churning water and squinted my eyes to see the number next to the red line.) “Thirteen degrees,” I replied. Natasha recorded the temperature in her log book.

I had joined my friend Natasha on a road trip along the Robert Campbell Highway. It was the Canada Day long weekend, 2023; however, we weren’t solely meeting for a fun catch-up and a leisurely camping trip. Natasha was conducting part of her research for her PhD at the University of Waterloo.

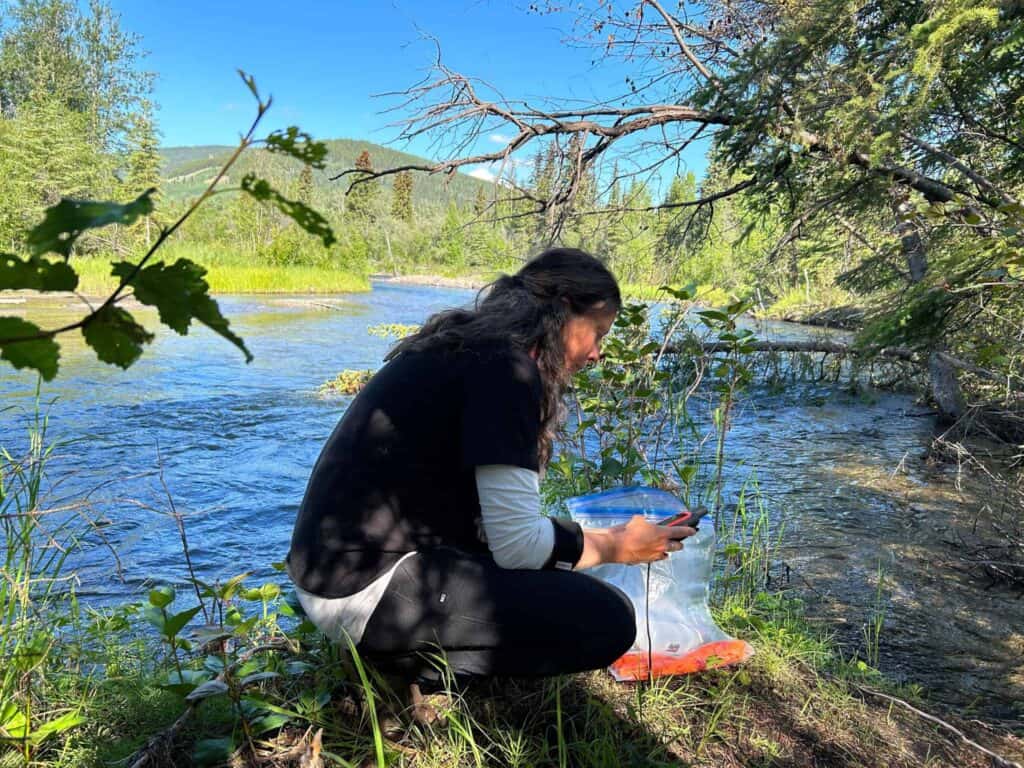

Natasha was not only testing the temperature of the water but, more importantly, she was collecting water samples so they could be analyzed for strontium isotopes.

Strontium is a pervasive element derived from riverbed rocks, and its levels and ratios are often unique to each river. In addition to being a unique marker for each river, strontium markers are also found in the calcified ear bones (the otoliths) of fish―and in the case of Natasha’s PhD study, in Chinook salmon.

Natasha is sampling the Yukon’s primary river systems and related waterways, as well as the otoliths of Chinook salmon, for her analysis. Based on the strontium imprint found in both the rivers and salmon, her research will help to identify where the Chinook salmon’s rearing and overwintering habitats are. The results may also help to identify the salmon’s disbursement patterns, their movement patterns and critical timings in their lifecycle. Currently, we don’t have this level of information in the Yukon, and without it, it’s difficult for us to know or anticipate the movements of juvenile salmon in their freshwater environment.

Natasha had already sampled a number of rivers and creeks across the Yukon. On this trip, we would be adding to her data by sampling nine more waterways, including the Pelly River, in two locations, as well as Drury Creek, Magundy River, Lapie River, Starr Creek, Mink Creek, Ketza River, Hoole River and the Big Campbell River.

To access these rivers, we drove 100 kilometres east of Carmacks and set up camp at Little Salmon Lake. From there, we drove farther east in the summer heat, through an impressive sprawling landscape. Aside from the road we drove on, the land was largely untouched and a powerful force unto itself and us travellers. The aspen leaves flickered in the bright summer’s light showering us with attention as we rolled down the gravel road.

We sampled the rivers in good company, with each of us having two dogs by our sides. The leg count in our respective trucks brought new meaning to the term 4×4! We agreed that, in addition to having much-needed space for our abundance of dogs, it was better to have the two vehicles for safety, in case something happened to the other.

We continued beyond Ross River, venturing onto the unpaved section of the Robert Campbell Highway. The dirt road wound its way through wetlands, around lakes and across charismatic rivers.

As we visited each river, it became apparent that they had their own unique personalities. The Lapie, a well-known paddler’s challenge, offered a dramatic canyon with rock side-walls that expressed like animal faces. Swallows swooped in and out of their nests on the opposite bank above the Lapie’s bright aquamarine water, which kicked up and swept past us as we ate lunch on the shore. Other rivers, like Starr Creek, were channelled with rip-rap boulders and culverts from the highway construction. Even so, looking just up or downstream told a wilder story, one of moss carpets, scratchy-barked spruce trees and surely a critter or two just around the bend.

We covered a long distance in a short period of time, and the weather changed with the landscape. Near the end of our easternmost extent at the Big Campbell River, about 180 kilometres from the Ross River turnoff, we encountered a dramatic lightning and rain storm that pelted our vehicles. Although extreme, the weather was exciting. The forked lightning decorated the sky in a momentary show, followed by low, deep rumbles and bursting raindrops. The storm cooled the air, a welcome change to the nearly unbearable heat of just moments earlier.

On our return drive west, away from the thick alders and even thicker mosquitos of the Big Campbell River, we continued sampling rivers. The confluence of the Hoole and Pelly rivers left a memorable impression on both myself and Natasha. We wandered down to the shore of the Pelly River, to get our bearings on how to sample the two merging water bodies. Staring back up at us from the rounded, grey river rocks was an endearing smiley face, perfectly arranged quartz etchings within a small, grey stone. Cherishing the unexpected and positive sign, we continued walking up the Hoole River, away from the confluence, to take samples.

As I knelt down on a curved boulder beside the Hoole’s edge, I felt invited by the sound of its rushing water. The water churned and swirled delightfully over submerged boulders. I felt drawn in. The more I watched the water, the more I felt I reached a new understanding of it.

The water was completely itself. It was fluid and moving this way and that. Parts of the river would circle around in a back-eddy, only to return and continue down the river’s mainstem. One thing was sure, the water never stopped being water: it kept flowing. I noticed how the water was not apologetic for being itself, it was 100 per cent elemental being. It was fully water at every juncture along its path, and it continued to be as water, no matter what landmark or impediment it came into contact with. It wasn’t thinking about how to be water, or which way to go … it simply was water.

It was as if the river was giving me permission to be 100 per cent my unique element. I felt encouraged to drop out of my brain’s chatter and down into my body—and immediately felt peaceful. An assured knowing washed over me. I suddenly knew where I came from, where I was going, and I felt at home with all of it. Amidst this feeling of belonging, I was reminded of the salmon that Natasha was researching. Their otoliths guide them from inception, to the ocean and return, over thousands of kilometres, all the way home―and always at home.